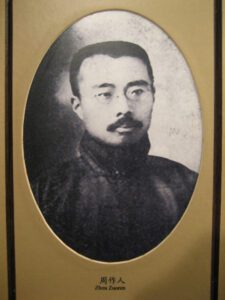

Chou Tso-jen Orig. Chou K'uei-shou T. Ch'i-ming H. Chih-t'ang Chou Tso-jen (1885-), essayist, scholar, and translator of Western works into pai-hua [the vernacular]. With his brother Lu Hsün (Chou Shu-jen, q.v.), he brought new prominence to the essay form in the 1920's and 1930's. Born in Shaohsing, Chekiang, Chou Tso-jen, like his two brothers, Lu Hsün (Chou Shu-jen, q.v.) and Chou Chien-jen, received his early education in the traditional Chinese classics. However, the family's financial position was impaired by the arrest and conviction of his grandfather in 1893 on charges of attempting to bribe a provincial examination official and by the death of his father in 1897. Chou Tso-jen was forced to leave the private school he had been attending and was sent to live with more fortunate relatives in Hangchow.

In 1898 and 1899 he passed the initial qualifying examinations for the sheng-yuan degree. However, he did not pursue an official career. Rather, he entered the Kiangnan Naval Academy at Nanking. He learned English at the academy, as well as marine engineering and military technology. At this time, Yen Fu, Lin Shu, and others were translating Western works into Chinese, and Chou became more interested in Western social and cultural history than in naval studies. His translation of The Gold Bug appeared in the magazine Hsiao-shuo lin [a forest of fiction] in 1905. He also produced an undistinguished novelette, Ku-erh chi [the orphan], which reflected his reading of Su Man-shu's translation of Les Miserables. Late in 1905, Chou Tso-jen went to Peking, where he competed successfully in examinations for a government scholarship to study abroad. Six months later he was graduated from the naval academy at Nanking. He then accompanied his elder brother, Lu Hsün, to Japan, where he studied Japanese at Hosei University. Later, he transferred to Rikkyo University to begin the study of English literature. He also studied classical and modern Japanese literature and classical Greek literature.

Chinese political refugees in Japan stirred student interest in political and social problems. Ch'ien Hsuan-t'ung (q.v.) arranged for Chou Tso-jen, Lu Hsün, and a few of their associates to meet regularly with Chang Ping-lin (q.v.), who lectured to the group on both political and philological matters. Chou, Lu Hsün, and a few friends attempted unsuccessfully to found a literary magazine which would also aid national survival. Chou translated one of H. Rider Haggard's novels and Maurice Jokai's Egyaz Isten. These were published in Shanghai in 1907 and 1908, respectively. In 1910 he translated Jokai's A Sarga Rozsa, but his translation was not published until 1920. Chou's Yü-wai hsiao-shuo chi [a collection of foreign fiction], to which Lu Hsün contributed a preface and a few translations, appeared in 1909 in two volumes. The selections were drawn mainly from the works of Eastern European authors, and the work was intended to arouse the people of China by making known the spirit of resistance of other peoples who suffered under oppressive rule and outmoded social institutions. Although the collection attracted little attention at the time of its publication, it was later to win the acclaim of literary critics.

Chou returned to China in 1912 with his Japanese wife, Hata Nobuku, and joined the Chekiang provincial education bureau as an inspector of schools. Six months later, he accepted employment as a teacher at the Provincial Fifth Middle School in Shaohsing. In addition to his teaching duties, in 1914 he translated Charcoal Sketches by Henryk Sienkiewicz ; he wrote a number of essays which were later included in the Erh-Cung wen-hsüeh hsiao-lun [essays on children's literature], published in 1932; and he cooperated with Lu Hsün in the compilation, editing, and private publication of old literary records and notes relating to their native place in Chekiang.

In January 1917, Chou Tso-jen moved his family to Peking, where he worked in the National History Compilation Office. In August of that year, he joined the academic staff of the college of arts of National Peking University. Under the administration of Ts'ai Yuan-p'ei, National Peking University was becoming a center of intellectual ferment. Ch'en Tu-hsiu (q.v.), the fiery radical and founder of the Hsin ch'ing-nien [new youth], was head of the college of arts; and Hu Shih (q.v.), an advocate of the language reform movement, was a member of the staff of the philosophy department. Chou Tso-jen began to write essays on current social and cultural issues, which regularly appeared in the Hsin ch'ing-nien and similar journals. As a proponent of language reform, he began to use the vernacular language in his essays, poems, translations, and scholarly publications. As early as January 1919, he began to experiment with new poetic forms. Many of his early experiments in pai-hua were written for children, and some had originally been written in Japanese. In 1922, a number of his vernacular poems were included in a book which also contained poems by Chu Tzu-ch'ing, Yü P'ing-po, Yeh Sheng-t'ao, Cheng Chen-to, and others. Although his poems were well received, Chou Tso-jen disclaimed any understanding of the requirements of poetic expression and henceforth devoted himself mainly to writing essays. The need for a Chinese literature freed from classical restraints and encumbrances and invested with a spirit of social realism was argued in many of his critical writings. Clear statements of the humanitarian principle that literature should strive to reflect the whole life of man, not avoiding the negative aspects of the human condition, were contained in essays entitled Jen ti wen-hsueh [humane literature] and P'ing-min ti wen-hsueh [literature of the common man]. His concern for the broader social aspects of the so-called Chinese renaissance movement was also clearly set forth in an essay in 1918 which advocated the emancipation of women and constituted one of the first clear expressions of principle in the movement to attain equality of the sexes. At the height of the anti-Confucian polemics following the May Fourth Movement, he deplored the superstitious and irrational elements of established doctrines, but recognized the human need for spiritual and moral nourishment.

The search for new values to replace the old stimulated interest in non-Chinese history and literature. The publication in 1918 of Chou's Ou-chou wen-hsueh shih [history of European literature], which dealt primarily with the Greek and Roman periods but also described pre-eighteenth century European literary developments, was followed during the next 15 years by 1 1 volumes of translations. These translations were significant for their use of the vernacular language but, even more, for their exploration of national literatures which had been ignored by the previous generation of Chinese translators. A Collection of Modern Fiction (1922), to which Lu Hsün and Chou Chien-jen also contributed, was drawn mainly from the shorter fictional works of Eastern European and Russian writers. A translation of Makar's Dream by V. G. Korolenko was published in 1926. These volumes were among the first of the great flood of translations of Russian and Eastern European novels, poetry, and drama produced in China in the 1920's and 1930's. A Collection of Modern Japanese Fiction (1923) was also a joint venture with Lu Hsün and contained 30 selections from the works ofsuch writers as Mushakqji Saneatsu, Mori Ogai, Akutagawa Ryunosuke, Natsume Soseki, Doppo Kunikada, and others. The attraction which ancient Greek literature had for Chou was reflected in his volume of translations of the lyric poetry of Herodes and Theocritus. Chou Tso-jen's stature as an authority on foreign literature was greatly enhanced by these publications and he was much in demand as a teacher and lecturer. During the years before the outbreak of war in 1937, he taught at Yenching University, National Peking University Women's College of Arts and Sciences, and Sino-French University.

Chou Tso-jen's prominence in modern Chinese letters was not solely attributable to his written works; he also played a major role in literary societies, which influenced the main literary trends of the period. In early 1921, the Wen-hsueh yen-chiu hui (Literary Research Society) was organized. Its constitution, drafted by Cheng Chen-to, and its inaugural manifesto, written by Chou Tso-jen, set forth the basic principles of the society. Other prominent members of the society were Mao Tun (Shen Yen-ping, q.v.), Kuo Shao-yü, Yeh Sheng-t'ao, and Sun Fu-yuan. In the early 1920's Sun Fuyuan was the editor of the literary supplement of the Peking Ctien Pao [morning post], to which Chou Tso-jen and Lu Hsün regularly contributed articles. A collection of Chou Tso-jen's essays, the Tzu-chi tiyuan-ti [one's own garden], which borrowed its title from Candide, was published in 1923. Containing some 50 essays embracing an extremely wide range of social and cultural comment, it became one of his most popular works. In November 1924, when the Literary Research Society was showing signs ofdisintegration, Chou Tso-jen, Lu Hsün, Ch'ien Hsuan-t'ung, Liu Fu (q.v.), Lin Yü-t'ang (q.v.), and Sun Fu-yuan formed the Yü-ssu she [threads of talk society]. In its founding statement of principles, the group denied any collective interest in the promotion of political ideals and declared its support of free thought and individual action. However, the contributors to its weekly journal, among whom Chou Tso-jen figured prominently, expressed themselves freely and frequently on cultural and political problems of the day. Chou strongly supported a literature which would encourage a revival of national morality and consciousness in order to restore international prestige to China. In other essays he lamented the corruption, self-deceit, lewdness, and self-abasing ways of the Chinese people, which, he argued, were responsible for social and political disorder.

In March 1926, following riots and labor strife which resulted in the death of 50 students, Chou Tso-jen and other Peking teachers and intellectuals were blacklisted for radical activities by the government of Tuan Ch'i-jui. Following the entry of Chang Tso-lin into Peking in April 1927, the Pei-hsin Book Company, the publisher of many of Chou Tso-jen's essay collections, was closed; the Yü-ssu journal was banned; and Li Ta-chao was arrested and executed. In October, Chou and Liu Fu were forced to take refuge in the home of the Japanese military attache. These experiences, combined with harsh attacks from leftist writers for his criticism of class and propaganda literary doctrines, resulted in Chou's gradual withdrawal from the main scene of literary life. Thereafter, he lived quietly in Peking, studying foreign and Chinese literature. He founded the magazine Lo-t'o ts'ao [camel grass] with his friends Yü P'ing-po and Hsu Tsu-cheng and continued to write essays, but the burden of his comment became increasingly narrow and personal. The essay Pi-hu tu-shu lun [on reading behind closed doors], dated 1927, reflected this shift from the critical essay to personal reflections on recondite matters and recollections of the past. In the work Chung-kuo hsin wen-hsueh tiyuan-liu [the origins of modern Chinese literature], which grew out of a series of five lectures delivered at Fujen University in March 1932, Chou argued that the emergence of the so-called proletarian literature movement in China represented a reversion to authoritarian concepts of the past. After the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in the summer of 1937, Chou Tso-jen remained in north China. Late in 1939 he was appointed dean of the faculty of literature at Peking University. A year later, he was named to head the bureau of education in the Japanesesponsored government in north China. Chou's reasons for remaining in north China during the period of the Japanese occupation remain a matter of dispute. He doubtless was influenced by personal and family considerations, and may have felt that his presence there would help to preserve Peking University from Japanese depredations. He also had a deep regard for some aspects ofJapanese culture. In any event, he continued to write essays, and several volumes of his writings were published at Shanghai, Tientsin, and Peking during the war years. That he also retained his interest in traditional Chinese culture was evinced by his detailed review of a book translated by Derk Bodde, Annual Customs and Festivals in Peking, which appeared in the first number of the Kuo-li hua-pei pien-i-kuan kuan-k'an [journal of the north China translation bureau] in October 1942. After the cessation of hostilities in 1945, Chou Tso-jen was arrested by the National Government authorities, tried in Nanking as a collaborator, and sentenced to death. He was not executed, however; his sentence was reduced to 15 years imprisonment, allegedly on the intercession of Li Tsung-jen and Hu Shih. A full pardon was accorded him by acting President Sun Lien-chung in February 1949. After his release, he lived in Shanghai for a time and then moved back to his old house at Peking. His wife died at Peking in 1962. Advancing years did not dim Chou's interest in literary matters, and in 1953-54 he published two volumes dealing, respectively, with Lu Hsün's early life in Chekiang and with the prototypes of Lu Hsün's fictional characters. He published a new Chinese translation of the Kojiki [record of ancient matters], an eighth-century Japanese work dealing with early Japanese myths and legends.

In the course of a varied and versatile literary career, Chou Tso-jen completed some 30 separate collections of prose essays, upon which his fame as a writer rests. In essays published before 1930 Chou helped to define the new literature in moral and psychological terms, much as Hu Shih had done in historical perspective. Chou's writings of this period reflected the influences of Freud, Frazer, and Havelock Ellis. As a member of Lin Yü-t'ang's circle in the 1930's, Chou became a spokesman for a skeptical Confucianism, tolerant of everything except stupidity and barbarism. With Lu Hsün, Chou Tso-jen brought the essay to new prominence in the 1920's and 1930's and thereby made a distinctive contribution to his era. An analysis of Chou's literary development by D. E. Pollard, "Chou Tso-jen and Cultivating One's Garden," appeared in Asia Major in 1965.

Chou Chien-jen (1889-), Chou Tso-jen's younger brother, was trained as a biologist and worked as an editor of the Commercial Press at Shanghai. His Chinese translation of Darwin's Origin of Species appeared in 1947. In 1948 he served in the education department of the Communist North China People's Government. After 1949 Chou Chien-jen held editorial, scientific, and cultural posts in the Central People's Government. From 1954 to 1958 he served as vice minister of higher education at Peking. In January 1958 he succeeded Sha Wen-han as governor of his native province of Chekiang. That year he also became president of the provincial branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Chekiang. During the post- 1949 period Chou played a prominent role in two non-Communist political parties, the China Democratic League and the China Association for Promoting Democracy, rising to become a vice chairman of the latter organization in 1955. He became head of the China-Nepal Friendship Association in 1956.

周作人

原名:周櫆寿 字:启明 号:知堂

周作人(1885—),散文家、学者,西方文学作品的白话文译者,他和他哥哥鲁迅,使二十年代、三十年代的散文达到一个新的显著地位。

周作人生在浙江绍兴,他与两个兄弟鲁迅(周树人)和周建人都在幼年时受旧式教育。1893年他祖父因被控试图行贿省监考官而下狱,1897年他父亲又去世,家道中落。周作人不得不辍学离开家乡,去杭州依附他的富裕的亲属。

1898—1899年考上秀才,但并不因此登上仕途,而到南京进了江南水师学堂,在那里学了英文和船舶工程及军事技术。那时,严复、林纾等人将西方作品翻译成中文,周作人对西方的社会和文化历史较之学习水师更有兴趣。1905年在《小说林》上发表了他的译作《金甲虫》,他还写了一篇短篇小说《孤儿记》,这是他在读了苏曼殊翻译的《悲惨世界》后写的。

1905年,周作人到北京,参加公费留学考试,考试合格。六个月后,他毕业于南京水师学堂,就和他哥哥鲁迅一起去日本,先在法政大学学日文,后进立教大学学英国文学。同时还学日本的古典和现代文学和希腊古典文学。

留日的中国政治避难者,常在学生中激起他们对政治社会问题的兴趣。钱玄同设法使周作人、鲁迅等人和章炳麟经常见面,章给他们讲授有关政治和语言学的问题。周作人、鲁迅和少数几个朋友试图办一份有助于民族复兴的文学杂志,但未成功。周作人翻译了哈格特的小说和裘开的小说,1909年出版他的《域外小说集》二卷,鲁迅写了序言,内有鲁迅的几篇译作。这本集子主要选自东欧作家的作品,希望中国人民了解在旧社会制度下其他被压迫人民的反抗精神,以唤醒中国人民。该书在出版的当时并未引起注意,以后才赢得文学评论家们的赞赏。

1912年,周作人和他的日本妻子羽太信子回到中国,在浙江省教育厅当督学,六个月后,到绍兴省立第五中学教书。他在教书之余,于1914年翻译了显克微支的《木炭素描》,他写作的一些短篇文章收集在1932年出版《儿童文学小论》一书中。他和鲁迅一起编辑和出版古文献和绍兴地方志。

1917年1月,周作人全家迁居北京,在国史馆工作。8月,进北京大学文科教书。北京大学在蔡元培主持下,正成为一个文化活动中心。激进分子、《新青年》主办人陈独秀,是北京大学文科主任,文学改良运动的创导者胡适是哲学系教员。周作人开始写作有关社会和文化问题的文章,在《新青年》和其他杂志上发表。他是文学改革的拥护者,所以他用白话文写文章、诗歌、译作以及学术论文。早在1919年1月,他就尝试新诗体裁。他的早期白话文章大都是有关儿童的作品,有一些原文是用日文写的。他的一些白话诗,和朱自清、俞平伯、叶圣陶、郑振铎等人的诗编在一起,于1922年出版了一本诗集。周作人的诗虽然受到读者的欢迎,但他并不想用诗来表达思想,因而主要是从事写作散文。中国文学需要从旧束缚中解脱出来,而用社会现实主义的思想加以充实,这是他在许多评论性文章中的论点。他认为文学应该反映人们的全部生活,也包括人们处境的消极方面,这种有关人文主义的观点,在他的《人的文学》、《平民的文学》等文章中表述出来。他从更广泛的社会方面来考虑所谓中国文艺复兴运动,他在1918年的论文中说得很清楚,他主张妇女解放、男女平等。随五四运动的反孔高潮之后,他斥责固有道德训条中的迷信和不合理的部分,但又认为人类需要有道德和精神的熏陶。

周作人在国外文学和历史中,追求新价值来代替他对古典作品的兴趣。周作人的《欧洲文学史》于1918年出版,该书主要是论述希腊和罗马时期,以及涉及十八世纪前欧洲文学的发展。此后十五年中,他出版了十一卷译作,这些译作在运用白话文,以及发掘民族文学方面的意义是很大的,因为这些作品是过去的翻译者所忽略的。周作人和鲁迅合编的《现代小说集》(1922年出版),所选的主要是东欧和俄国作家的短篇作品。1926年出版的柯罗连可的《马加的梦》的译本。这些译作是二十年代、三十年代中,在中国大批涌现俄国和东欧小说、诗歌、剧本的译本的前期作品。1923年出版的《近代日本小说集》,也是和鲁迅共同编选的,其中有武者小路、森鸥外、芥川龙之介、夏目漱石、国木田独步等人的作品三十篇。周作人对古希腊文学也很有兴趣,这从他翻译希罗多德和希荷克利斯的抒情诗中可以看得出来。他的这些出版物,使他拥有了外国文学的权威地位,许多学者请他去讲课。1937年战争爆发前他曾在燕京大学、北平女子文理学院、中法大学任教。

周作人在近代中国文学界的名望,不仅因为他有许多著作,而且在一些对当时的文学倾向有影响的社团中起重要作用。1921年初“文学研究会”成立了,会章由郑振铎拟订,发起缘由系周作人撰写,说明了该会的宗旨,该会的其他知名人士有茅盾、郭绍虞、叶圣陶、孙伏园。二十年代初,孙伏园编辑北京《晨报》文学副刊,周作人和鲁迅经常为该刊投稿。1923年出版了周作人的文集《自己的园地》,收集了他的五十多篇纵论社会文化等问题的文章,是一本广为流传的著作。1924年11月,“文学研究会”趋于分裂,周作人、鲁迅、钱玄同、刘复、林语堂、孙伏园组成了“语丝社”。在成立宣言中,声明该社同人并无共同推动政治思想的打算,而主张支持自由思考和独立行事。周作人为该社周刊撰稿,该刊的撰稿者经常对当前政治和文化问题自由发表各自的意见。周作人竭力主张文学必须重整民族道德和良知,以恢复中国的国际声誉。在另一些文章中,他哀叹中国人的腐败、自欺、乱谣、自卑等现象,他认为这是造成社会政治动乱的根源。

1926年3月,在北京发生骚乱五十名学生死亡。周作人等教师和知识界人士,因被段祺瑞政府认为是过激分子,列入黑名单中。1927年4月,张作霖进占北京,出版不少周作人书籍的北新书局关闭,《语丝》杂志被封,李大钊被捕处死。10月,周作人、刘复避居在日本武官家里。周作人遭此经历,又由于他批评文学为阶级斗争进行宣传的主张遭到左派作家的严厉批评,周作人逐渐退出文学界。他隐居在北京,研究中外文学,和友人俞平伯、徐祖正办了一份杂志叫《骆驼草》,继续写文章,但是格调渐趋狭窄仅及于身边琐事。1927年写的《闭户读书录》这篇文章,反映了他从写评论文章、转到黯淡的反省和往事的回忆。《中国新文学的源流》一书,是1932年3月他在辅仁大学作讲演时的五篇讲稿的集子。他认为中国的所谓无产阶级文学运动的出现,表示对过去权威思想的一次审订。

1937年夏中日战争爆发后,他仍留在北京,1939年被任命为北京大学文学院院长,一年后,又任华北政务委员会教育总署督办。周作人为什么在日本占领期间留在华北,是广为争论的问题。当然有种种个人和家庭的原因,他也许还认为他留在那里可以使北京大学免于遭日本人的劫掠。当然,他对日本文化的某些方面是深为尊崇的。他继续写文章,战争期间,在上海、天津、北京还出版了几册他的作品集。他对中国的传统文化仍很注意,1942年10月《国立华北编译馆馆刊》上有一篇周作人对博德翻译的《北京的风俗节期》一书的详细评论。

1945年中日战争结束,国民政府当局逮捕周作人,在南京以投敌罪被判处死刑,但未执行,改为十五年徒刑,据说这是因李石曾、胡适的疏通。1949年由代总统孙连仲(原文如此,应为李宗仁——译注)给以赦免。周作人被释后,在上海住了一些时候,又迁回他北京的故居,他的妻子在1962年去世。在以后岁月中他对文学的兴趣并未减退,1952—1954年他出版了两本书:一本是有关鲁迅早年在浙江的生活,一本是有关鲁迅小说中的人物原型。他还出版了一本有关八世纪日本神话传奇的著作《古事记》的中译本。

周作人在文学界的多种多样经历,完成了三十多部散文集,就此而论,他作为一个作家是当之无愧的。周作人在1930年前发表的文章从道德和心理范畴来阐明新文学,而胡适则从历史学的范畴来论述。周作人这一时期的作品,受弗洛依德、法朗士和霭理斯的影响。他在三十年代是属于林语堂一派的人物,他成为这批人的代言人,怀疑儒家学说,主张宽容而反对愚暴。他和鲁迅一起,使二十年代、三十年代间的散文达到了一个新高峰,对他那个时代作出了卓越贡献,波拉在1965年《亚洲大众》杂志上发表文章,评论周作人的文学生涯时说:“周作人垦殖了他的园地”。

周建人(1889—),周作人弟弟,是生物学家,曾任上海商务印书馆编辑。1947年出版了他的达尔文《物种起原》的中译本。1948年,他在共产党华北人民政府教育部任职。1949年后,他在中央人民政府任编辑、科学、文化方面的职务。1954—1958年在北京任高教部副部长,1958年1月继沙文汉任浙江省主席,兼任中国科学院浙江省分院院长。1949年后,他在中国民主同盟和中国民主促进会两个非共产主义政党中任重要职务,1955年升任为中国民主促进会副主席。1956年任中尼友好协会会长。