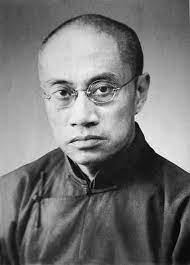

Liang Shu-ming (9 September 1893-), attempted a new formulation of Confucianism while teaching at Peking University in 1917-24. From 1927 to 1937 he was a leader in the rural reconstruction movement. Thereafter, he was active in "third force" politics and helped to form the coalition that became the China Democratic League. Although he lived in the People's Republic of China after 1949, he refused to accept Marxism-Leninism as a valid ideology for China.

A native of Kweilin, Kwangsi, Liang Shuming was born and raised in Peking. His father, Liang Chi, w as a respected metropolitan official who established rehabilitation and vocational schools for convicts and poor children. Liang Shu-ming attended a modern primary school, where he learned English, the Shun-t'ien Middle School, and the Chihli Public Law School. During his student days, he was attracted to utilitarianism. On the eve of the revolution in 1911, he joined the Peking- Tientsin chapter of the T'ung-meng-hui and helped smuggle bombs and rifles to the revolutionaries. In 1912 he worked as a reporter for the Tientsin Min-kuo pao [republican newspaper] . In 1 9 1 3 because offamily disagreements and his own disillusionment with the republican cause, he turned to wei-shih, or "consciousnessonly," Buddhism and spent three years in semiseclusion. In 1916 Liang Shu-ming became the private secretary of his relative Chang Yao-tseng, who was serving as minister of judicial affairs at Peking. Ts'ai Yuan-p'ei (q.v.), who had been impressed by an article on Buddhism which Liang had contributed to the Tung-fang tsa-chih 'Eastern Miscellany), soon invited him to join the faculty of Peking University. Liang accepted this offer in 1917, when Chang Yao-tseng was forced out of office by Chang Hsün (q.v.) during Chang Hsün's attempt to restore the Ch'ing dynasty to power.

Liang Shu-ming reexamined his beliefs in 1918 after his father committed suicide. He came to believe that thought must always vindicate itself by providing a view of life which is personally satisfying and a general explanation of society and social problems which can serve as a blueprint for action. He turned from both utilitarianism and Buddhism to his own version of Confucianism.

After formulating and presenting his Confucian ideas in lectures, Liang published Tunghsi wen-hua chi ch'i che-hsueh [the cultures of East and West and their philosophies] in 1921. Seeking to show that Chinese cuhure was relevant to the modern world, he identified the West, China, and India as three basic cultural types, ultimately differentiated from each other by the subjective attitude, or will, which informs and characterizes the attempts of each one to solve the problems posed by its environment. According to Liang, the Western will, the "attitude of struggle," seeks to wrest the satisfaction of its desires from the external world or from other people; the Chinese attitude is one of harmonization and satisfaction through adjustment; and the Indian attitude is escapist, recognizing the futility of desire and the search for satisfaction. Liang held that these cultural wills succeeded one another in dialectical sequence. Western culture was then in the ascendant, but it would give way to the Chinese, resulting in a higher world civilization which would mold the scientific and material successes of its predecessor to man's intuitional, moral, and ethical nature. In the distant future, the Indian attitude would displace the Chinese attitude, and another new era would begin. Because the Tung-hsi wen-hua chi ch'i che-hsueh attempted to break through the iconoclasm of the Literary Revolution and the May Fourth Movement and to affirm the relevance of the past to the solution of contemporary Chinese problems, its publication resulted in heated controversies about the worth of traditional values, the function of religion, and the nature of culture and cultural change. However, Liang's views did not receive much support. He himself was dissatisfied with the book, and he later had it removed from circulation for three years. He planned an emended version of the work, but it never appeared. Liang Shu-ming left Peking University in 1924 and became the principal of a middle school in Ts'aochou, Shantung. In accordance with his theories, he hoped to institute a new kind of education which would achieve ethical as well as intellectual development through the fellowship of faculty and students. He also hoped to found a university, but his plans soon foundered. He returned to Peking in 1925, where he spent two years living with a small group of students and seeking a worthwhile program in which to participate. He soon became interested in the rural reconstruction movement.

Liang worked for a time as head of the Kwangtung-Kwangsi reconstruction committee and visited the major reconstruction projects in China. Early in 1930 he resigned from office to join P'eng Yü-t'ing and Liang Chung-hua in establishing Honan Village Government College. He also edited the Ts' un-chih yueh-k'an [village government monthly]. The project collapsed soon after Han Fu-chü (q.v.), the governor of Honan, was transferred to Shantung. Han soon invited all of the men who had been associated with the Honan project to found a similar institution in Shantung. The Shantung Rural Reconstruction Research Institute was founded in 1931, and Liang Shu-ming served as its guiding spirit until 1937. Liang regarded the Shantung project, which exercised direct control over Tsoup'ing hsien and Hotse hsien and which operated in a lesser way throughout the province, as the necessarily small beginning of a nation-wide movement rather than as an experiment of limited scope. By this time, Liang no longer believed in the cultural dialectic set forth in the Tung-hsi wenhua chi ch'i che-hsueh. He now argued that because China was different from Western nations, it would be wrong to import such Western political systems as democracy and Communism. He denied the validity ofapplying Marxist class analysis to China and held that the derangement of Chinese society in the name of class struggle was the result of the irresponsible actions of men who were using Marxist theory to obtain power for themselves. Accordingly, besought, through the Shantung program, to ameliorate social relations peacefully by creating through education an enlightened leadership of intellectuals and the peasant masses and integrated institutions which would combine the functions of local self-government with economic cooperation. He believed that education of the correct sort would obviate the need for revolution. However, Liang was unable to test his theories for any length of time because the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in 1937 forced the Shantung Rural Reconstruction Research Institute to close.

During the early war years, Liang served on the National Defense Advisory Council and its successor, the People's Political Council. After touring Communist-held and front-line areas, he became convinced that the Kuomintang- Communist united front was in jeopardy. Accordingly, in November 1939 he helped to found the T'ung-i chien-kuo t'ung-chih hui [united association of comrades for national construction] to act as a third force in pohtics and to maintain the united front. The organization was composed of representatives from such minor pohtical parties as the China Youth party and the National Socialist party. In 1941 it was superseded by the League of Chinese Democratic Political Groups {see Chang Lan). Liang went to Hong Kong to establish and edit the league's newspaper, Kuang-ming pao [light], which began publication in September. Its staff included Huang Yen-p'ei, Hsü Fu-lin, and Shang Yen-ch'uan. When Hong Kong fell to the Japanese in December, the Kuang-ming pao was forced to suspend publication.

In January 1942 Liang Shu-ming took refuge in Kweilin, where he remained until a Japanese offensive in the summer of 1944 forced him to flee again. By October 1945 he had reached Chungking and had become secretary general of the China Democratic League, the successor of the League of Chinese Democratic Political Groups. He held this office until October 1946, by which time he had alienated the Chinese Communists by proposing National Government occupation of the main Manchurian rail lines and had angered the Kuomintang by investigating and writing a report on the assassination in Kunming of the prominent liberals Wen I-to (q.v.) and Li Kung-p'u. After retiring from office, Liang remained in Chungking, writing, teaching, and occasionally expressing his views in newspaper articles. After declining to participate in the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference of September 1949, held to establish the Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China, Liang Shu-ming emerged from retirement in January 1950 to accept nomination as a specially invited delegate to the National Committee of the conference. During the next few months he traveled extensively, observing rural work in Hopei, Shantung, and Szechwan. In October 1951 he published in the Kuang-ming jih-pao a lengthy statement entitled "Changes I Have Undergone in the Past Two Years," which was a recognition of Chinese Communist successes, a restatement of his earlier views, and an explanation of why his viewpoint had not changed. In answer to criticisms of this article, Liang said that he was open to persuasion but that his critics had not dealt substantively with any of the crucial issues on which he differed with the Chinese Communists. In 1953, at a high-level meeting of Chinese Communist leaders, Liang strongly criticized the differences in the living standards of workers and peasants. He was hooted off the rostrum, and it was only because Ch'en Ming-shu (q.v.) intervened on his behalf that more serious steps against him were not taken. In the wake of the Communist-sponsored campaigns against Hu Feng and Hu Shih in 1955, Liang became the target of scores of articles, study meetings, and demonstrations. He was denounced as an outstanding example of feudal reaction and its philosophic handmaiden, subjective idealism, whose political function was to dull the consciousness of the masses. He also was identified as a partner and accomplice of Hu Shih. Liang remained silent until February 1956, when he announced that although he had welcomed criticism, he had experienced difficulty in subduing the urge to resist. He went on to say that his understanding of Marxism had improved and that he was continuing to study. He refrained from criticizing the government during the Hundred Flowers campaign, thus escaping criticism during the ensuing anti-rightist movement. Among Liang Shu-ming's important works are the Shu-ming su-ch'ien wen-lu [Liang Shuming's essays: 1915-1922], the Shu-ming su-hou wen-lu [Liang Shu-ming's literary compositions written after the age of 30], the Chung-kuo min-tsu tzu-chin yün-tung chih tsui-hou chueh-wu [the final awakening of the Chinese people's self-salvation movement], the Hsiang-ts'un chien-she li-lun [theory of rural reconstruction], the Liang shuming chiao-yü lun-wen chi [Liang Shu-ming's collected essays on education], and the Chung-kuo wen-huayao-i [essentials of Chinese culture]. Little is known about Liang Shu-ming's personal life. He was married sometime after 1918 and is known to have had two sons.

梁漱溟

号:焕鼎

梁漱溟(1893.9.9—),他于1917—1924年在北京大学教书时曾对儒家学说重作诠释。1927—1937年,他是乡村建设运动中的首领,其后在“第三势力”的政治活动中很活跃,又在组织民主同盟活动中起了作用。1949年后住在中华人民共和国,但不承认马列主义是中国的有效的意识形态。

梁漱溟原籍广西桂林,他本人生长在北京。他父亲梁巨川是一个为人敬重的京官,为罪犯和贫苦儿童办过职业学校。梁漱溟进了新式学校,学了英语,后又进顾天中学,直隶法政学校。他在学生时代就倾心于功利主义,1911年革命前,他加入了同盟会京津分会,为革命党人私运弹药枪枝,1912年为天津《民国报》记者,1913年因家庭不和又对共和革命感到幻灭而潜心于佛教唯识宗,过了三年半隐居生活。

1916年,粱在北京充当他的亲戚司法总长张耀曾的秘书。蔡元培赏识他给《东方杂志》写的关于佛教的一篇文章,请他到北京大学当教师。1917年张勋复辟时,张燿曾为张勋所迫去职后,梁就接受了蔡元培的聘请。

1918年,他父亲自杀后,他重新思考自己的信仰,反复证明自己思想的正确性。他认为,思想应能提供一种人生观,它既能自我满足又能对社会和社会问题作出总的解释并能提出行动方案。由此,他从功利主义和佛教观点二者转向他自行诠释的儒家学说。

梁漱溟形成了自己的儒学观点并在讲课中加以闸述,于1921年出版了《东 西文化及其哲学》一书,他为了表明中国文化是同近代世界有关的,他把西方文化、中国文化、印度文化并列为三种基本的文化形态,就主观态度或意愿而论,它们是迥然不同的,这种不同说明它们为解决周围环境所提出的问题作了不同的努力。梁漱溟认为,西方的意愿即“奋斗的态度”追求的是从外部世界或其他民族方面实现自己的愿望;中国的态度是用调整的方法来取得和谐和満足;印度的态度是逃辟现实,认为意愿和求取満足都是徒劳的。梁漱溟认为这几种文化意愿是按照辩证的顺序前后继起的。西方文化当时正在上升,但必将让位于中国文化而出现更为高级的世界文化,它把前人的科学的和物质的成就与人类直现的、道德的、伦理的品质相融合。在遥远的将来,印度文化将取代中国文化而出现另一个新时代。

《东西文化及其哲学》一书,意在打破文学革命和五四运动的偶像崇拜,并且确认解决当代中国问题必须肯定过去,因此,此书出版后,引起了关于传统观念的意义、宗教的作用、文化的性质及其变化等问题的热烈争论。但是,梁漱溟的观点并没有多少人赞同,他本人对该书也觉得不满意将它停止发行三年,搜准备修订后再版,但終未实现。

梁漱溟于1924年离开北京大学到山东曹州的一个中学当校长。依据他的理论,他希望通过该校师生的努力创立一种能发展品德和智力的新教育,他还计划筹办一所大学,但未能实现。1925年,他又回到北京,与一小批学生住在一起,寻求从事一些有意义的事业。不久他对乡村建设运动发生了兴趣。

梁湫溟曾一度担任两广建段委员会主任,考察了国内一些主要的建设项目。1930年初,他辞职,与彭雨亭、梁仲华办了一所河南乡村建设讲习所,同时主编《村治》月刊。这个计划,因河南省主席韩复榘调到山东而告失败。韩不久邀请所有在河南经办这一计划的人员去山东建立同样的机构,1931年,“山东乡村建设研究院”开办,到1937年为止,梁漱溟是其精神上的领袖。梁漱溟认为在邹平县和荷泽县,以及在较小的程度上在全省实行的山东计划,不仅是一次小规模的实验,更是一次全国性运动的必要的小小开端。

当时,梁已不再坚持《东西文化及其哲学》一书中关于文化的辩证发展观点,如今,他认为东西文化是不同的,因此输入民主主义、共产主义等西方政治制度是错误的。他认为不能把马克思主义阶级分析方法运用于中国社会,以阶级斗争为名扰乱中国社会,乃是那批想用马克思主义理论攫取权力的人的不负责任的行动所造成曲。因此,他想用在山东实行的计划和平地改善社会关系,其方法是通过教育建立起知识分子和农民群众的开明的领导,以及能够把地方自治和经济合作综合在一起的混合机构。他相信用正当的教育手段可以消除人们对革命的需耍。但是他没有较长的时间实现自己的计划,因为1937年中日战争爆发,山东乡村建设研究院被迫停办了。

战争初期,梁在国防谘议会及其后的国民参政会任职,他在考察共产党根据地和前线后,深感国共的统一战线处于危急之中,因此,他于1939年11月参与成立了“统一建国同志会”,以第三势力的身份从事政治活动,维护统一战线。该会包括了一些小党派如青年党,民社党的代表。1941年,该会由民主政团所替代,梁去香港主编该政团于9月出版的《光明报》,编辑部中有黄炎培、张云川等人。12月香港沦陷,《光明报》披迫停刊。

1942年1月,梁逃到桂林,1944年夏因日军进攻,梁又被迫离去。1945年10月到重庆,任民主同盟秘书长,这个同盟是中国民主政团同盟的后继者。他担任此职直至1946年10月。这时,他既因建议国民政府进占东北主要铁路线而疏远了共产党,又因调査及撰写着名的自由主义分子闻一多、李公朴在昆明被暗杀情况的报告而激怒了国艮党。梁漱溟离职后,留在重庆,从事写作和教书,偶然也在报纸上写些文章发表自己的见解。

梁漱溟不愿参加1949年9月为建立中华人民共和国而召开的中国人民政治协商会议,1950年1月他开始出头露面,成为政协全国委员会的一名特邀代表。此后数月中,他广为旅行,考察了河北、山东、四川的乡村工作。1951年10月,他在《光明日报》上发表了长篇文章《两年来我有那些变化》,承认中国共产党的成就,重述了他过去的观点,并说明何以他的观点未有变化。为了回答对他的批评意见,梁漱溟声称,他愿承听取别人的意见,但是批评者并没有真正涉及他与中国共产党分岐的任何一个重大问题。

1953年在一次共产党领导人的高级会议上,梁漱溟强烈批评工农之间生活水平上存在的差异,被轰下讲台,幸有陈铭枢为他解围,才免受严厉处置。1955年共产党领导的批判胡风、胡适的运动中,梁漱溟也成了很多文章、学习会议中受攻击的一个目标,他被斥为反动的封建势力的突出代表,是哲学主观唯心主义的侍女,这种哲学的政治作用是麻痹群众的思想。人们还指斥他和胡适是一丘之貉。梁保持沉默到1956年2月,那时,他声称他虽然欢迎批评,但又难于抑制抗拒的心情。他又说,他对马克思主义的认识已有所改进,愿意继续学习。在百花齐放运动中,他控制自己不再对政府进行批评,因而在反右运动中免于受到批判。

梁漱溟的重要著作有《漱溟州前文录》(1915—1922)。《漱溟州后文录》、《中国民族自救运动之最后觉悟》、《乡村建设理论》。《梁漱溟教育论文集》、《中国文化要义》。

梁漱溟的个人生活不详,他于1918年前后结婚,据说生有两子。