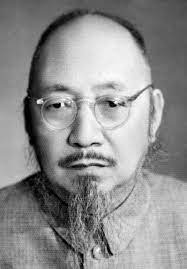

Liu Ya-tzu (May 1887-June 1958), the last outstanding poet of the traditional school. He also was known as a scholar and as the founder of the Xan-she (Southern Society).

Born in the Wuchiang district of Soochow, Liu Ya-tzu came from a land-holding literary family whose property provided means to educate several generations of its male members in the scholar-gentry tradition. His father, Liu Xien-tseng (1866-1912j, was a sheng-yuan, and his uncle was a scholar of mathematics and an expert calligrapher. Liu Ya-tzu began the study of the Confucian classics and T'ang poetry under his mother's guidance. By the age of 1 1 , he had begun to compose poetry and historical essays.

Having acquired a good classical education, Liu Ya-tzu distinguished himself by passing the sheng-yuan examination at the age of 15 (1902). Like many young men of his generation, he came under the influence of the reform movement led by K'ang Yu-wei and Liang Ch'ich'ao (qq.v.) and soon was swept into the revolutionary movement aimed at the overthrow of the Manchus and the establishment of a republican government in China. In 1902 Chang Ping-lin, Ts'ai Yuan-p'ei, Wu Chih-hui, and others organized the Chung-kuo chiao-yü hui [China education society] in Shanghai to promote modern education in China. The following year, the young Liu Ya-tzu joined this society and became a student at its new school, the Ai-kuo hsueh-she [patriotic institute], headed by Ts'ai Yuan-p'ei. In 1904—5 he was a student at the Tzu-chih hsueh-she [self-government academy] and an instructor at the Chienhsing kung-hsueh [constant action public school] .

In 1906 he joined the T'ung-meng-hui, founded by Sun Yat-sen, and became active in revolutionary work by writing patriotic essays and poems. Liu Ya-tzu's most important activity in this early period, however, was the founding of the Xan-she (Southern Society), originally an association of southern Yangtze men of letters in the Soochow-Shanghai-Hangchow area. With such writers as Liu Ya-tzu, Ch'en Ch'üping, and Kao Hsü as charter members, the group held its first meeting in Soochow on 13 Xovember 1909. The society became nationwide in scope and attracted many well-known writers; its membership grew from about 20 to more than 1,000. The Southern Society, the last important rallying point of traditional literature in the republican period, was also known as a group of politically conscious writers with radical and nationalistic sentiments. Its members were not formally committed to any political ideology, but the participation of such men as Huang Hsing, Sung Chiao-jen, and Ch'en Ch'i-mei (qq.v.) lent a revolutionary hue to the society during the period of the anti- Manchu revolt of 191 1 and the early years of the Chinese republic.

In 191 1-12 Liu Ya-tzu was active as a journalist in Shanghai, editing several newspapers which supported the revolutionary cause, including the T'ieh-pi pao, the T'ien-to pao, the Ming-sheng jih-pao, and the T'ai-p' ing-yang pao. He also seived briefly as secretary in the office of Sun Yat-sen in Nanking, but soon left this position to return to journalism in Shanghai, where he wrote articles attacking the peace negotiations between the revolutionaries and Yuan Shih-k'ai. After Yuan's accession to the presidency in February 1912, Liu Ya-tzu abandoned his political activities in disgust and returned to Wuchiang.

Liu devoted himself for several years to a literary career, writing poems and essays and editing the publications of the Southern Society. The group held semi-annual meetings, usually in Shanghai, and regularly published collections of literary works by its members. Between 1910 and 1923, 22 collections of poems and essays written by Southern Society members were published in 23 volumes, in addition to a volume of stories in 1917. During this period, Liu Ya-tzu also assembled a comprehensive collection of the literature of the Wuchiang district. Hundreds of rare books and manuscripts had to be copied by hand, and Liu himself copied some of these.

As head of the Southern Society during most of the 14 years of its existence, Liu Ya-tzu associated with writers and political figures throughout China. The end of the Southern Society came ostensibly as the result of a controversy over the relative merits of T'ang and Southern Sung poetry. One group, represented by Liu Ya-tzu, favored the traditions of T'ang poetry, and, among modern writers, preferred the works of the nineteenth-century poet and reformer Kung Tzu-chen (ECCP, I, 431-34). Another group, represented by Ch'en San-li and Cheng Hsiao-hsü (qq.v.) favored the "T'ung-Kuang" (T'ung-chih and Kuang-hsü, 1862-1908) style, w^hich traced its origins to the poetry of the Southern Sung period. The real reason for the controversy and subsequent end of the Southern Society, however, was Liu Ya-tzu's growing awareness of the inadequacy of the traditional Chinese literary language to express the ideas and aspirations of contemporary China. He was in full sympathy with the new movement, led by Ch'en Tu-hsiu and Hu Shih, which advocated the use of paihua [the modern vernacular] as a medium of literature. Liu himself changed to pai-hua in his prose writing, though he had to admit defeat in his attempts to write poetry in the vernacular. This change in Liu Ya-tzu's literary views finally led to his resignation from the Southern Society. In 1923 he organized the Hsin Xan-she (New Southern Society), a group which hoped to create a new literature for China by introducing significant currents of world thought to China and by reevaluating classical Chinese literature. The New S.outhern Society, however, had only limited success. Liu Ya-tzu was attracted to the new alignment of nationalist and revolutionary forces in south China. This was the period of the reorganization of the Kuomintang (1924) and the establishment of a new political regime in Canton. Liu, who had been promoting underground Kuomintang organizations in his native district, was made a member of the Kiangsu executive committee and head of the propaganda department. In 1926 he went to Canton to attend the Second National Congress of the Kuomintang; he was elected to the Central Supervisory Committee. However, he soon became disturbed by the attitude of Chiang Kai-shek, then military leader in Canton, toward the dispute between the party's left and right wings. A leftist member close to Liao Chung-k'ai, Liu Ya-tzu advocated the continuation of Sun Yat-sen's policies of admitting Communists to the Kuomintang as individuals and of alliance with the Soviet Union. Liu returned home from Canton, but he did not stay long; almost immediately he was forced to flee by Sun Ch"uan-fang, who was then in control of Kiangsu and east China. He remained for a few months in Shanghai, but was forced to escape to Japan in May 1927 at the time of the purge of Communist and leftwing Kuomintang elements by Chiang Kaishek. After almost a year of exile in Japan, Liu returned to Shanghai in April 1928. He refused to join the new National Government in Nanking, because he believed that its policies were at variance with those set forth by Sun Yat-sen in his final testament. Nevertheless, at the Fourth National Congress of the Kuomintang in 1931, he was reelected to the Central Supervisory Committee. In 1932 he was appointed head of the gazetteer office (T'ung-chih-kuan) of the Shanghai municipal government, and during the next few years he supervised the publication of several yearbooks and volumes of historical materials relating to Shanghai. »r- The outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war in mid- 1937 cut short these activities. For about three years Liu Ya-tzu Uved in Japaneseoccupied Shanghai, where he severed all political ties and led a secluded life, devoting himself to research on the members of the Ming imperial household who had resisted the Manchu conquerors in the second half of the seventeenth century. Liu Ya-tzu hurriedly left Shanghai in December 1940 because he was afraid he would be coerced into serving the puppet regime that had been established in Nanking in March 1940 under the leadership of Wang Ching-wei, the former Kuomintang leftist leader and sometime member of the Southern Society. Liu went to Hong Kong. At the time of the New Fourth Army Incident in January 1941, Liu sent a telegram to Chungking condemning the action as a serious threat to the wartime united front. He was expelled from the Kuomintang.

In December 1941, when the Japanese occupied Hong Kong, Liu Ya-tzu had to flee to the interior, abandoning his carefully collected library of materials on the southern Ming period. After traveling to a guerrilla base at Haifeng in southern Kwangtung, Liu Ya-tzu reached Kweilin in June 1942. For the next two years, he devoted himself almost entirely to literature and produced a large number of works. In 1944 he went to Chungking and returned to politics. He joined the China Democratic League in 1945; he also became a founding member of the San Min C^hu I Comrades Association and served as its chairman from 1946 to 1948. Liu Ya-tzu returned to Shanghai in late 1945. When postwar Kuomintang-Communist political tensions deteriorated into civil war, he found that because he was a member of the Democratic League he was not safe in Shanghai. He fled to Hong Kong in 1947 and joined a group of anti-Kuomintang dissidents. He participated in January 1948 in the organization of the Kuomintang Revolutionary Committee under the chairmanship of Li Chi-shen. In addition to Liu Ya-tzu, other prominent members of this group included Feng Yühsiang. Ho Hsiang-ning (the widow of Liao Chung-k'ai), and T'an P'ing-shan. In 1949 Liu moved to Peking, where he spent the remaining years of his life. After the Central People's Government was established, he served on its Government Council (1949-54). He also was a member of the standing committee of the National People's Congress (1954-58) and of the culture and education committee of the Government Administration Council. Because his health was poor, he avoided public functions and wrote very little, even cutting off family correspondence. He died of pneumonia in Peking in June 1958, at the age of 71. Liu Ya-tzu's principal contributions were in the realm of literature, especially poetry. He was one of the last outstanding poets of the traditional school and one of the most prolific writers of his age. He compiled only a few incidental volumes of his own writings, notably Ch'eng-fu chi [the raft], written in 1927-28, and Huai-chiu chi [remembrance of things past] of 1947. Most of his early poems and essays can be found in the twenty-odd collections of the Southern Society. A selection of his poetry, Liu Ya-tzu shih-tz'u hsuan, edited by his two daughters, Liu Wu-fei and Liu Wu-kou, was published in Peking in 1959. A devoted bibliophile and book collector, Liu Ya-tzu was also an indefatigable editor of his friends' literary remains, notably those of Su Man-shu (q.v.), whose collected works he published in 1928. Liu also enjoyed a poetical friendship with Mao Tse-tung, exchanging traditional verses with him on several occasions; and Liu may have had a hand in the composition of several of Mao's most famous poems, including "Snow — to the melody Ch' in-juan-ch' un," in which Mao by implication compares himself favorably with several major figures in Chinese history. Impractical in everyday affairs, Liu Ya-tzu was greatly dependent upon his wife, nee Cheng P'ei-i, whom he married in 1906. Throughout their long married life, she was his constant companion, accompanying him on his travels and sharing his misfortunes. A son, Liu W^u-chi (1907-), who was graduated from Tsinghua University, received a Ph.D. in English at Yale University in 1931 and later taught Chinese literature at Indiana University.

柳亚子

原名:柳慰高

字:人权

柳亚子(1887.5—1958.6),中国古体诗最后一个杰出的诗人。他又以学者和南社的创始人而知名。

柳亚子出生在苏州吴江县的一个世代书香的绅士之家。他的父亲柳念曾(1866—1912)是一个秀才,叔父是数学家和书法家。柳亚子幼年时在母亲的训诲下习读儒家典籍和唐代诗词,十一岁起,就学习写诗撰文了。

1902年柳亚子十五岁时应县试中秀才,他和当时的一些青年一样,受到康有为、梁启超等改良主义维新运动的影响,不久又卷入推翻满清建立民国的革命活动。1902年章炳麟、蔡元培、吴稚晖等人在上海创设“中国教育会”,着手推行现代教育,翌年,年青的柳亚子加入了“教育会”进入蔡元培主办的新式学校“爱国学社”求学,1904—1905年,柳亚子先在“自治学社”上学,后在“健行公学”教书,1906年加入孙逸仙创立的同盟会,他用写作爱国诗词和文章积极投入革命运动。

柳亚子早期最重要的活动是他组织了一个“南社”。它起先是江南沪、杭、苏一带文人结成的一个团休、柳亚子、陈去病、高旭是其中前主要人物,1909年11月13日在苏州第一次聚会,以后逐新成为一个全国闻名的社团,吸引了不少著名作家参加,从最初的二十余人发展到一千多人。南社,这个民国时期的传统文学的最后一个重要集结点,也以其成员的激进的民族主义情绪而知名。它的成员原来并不正式信奉棊种政治观点,但是黄兴、宋教仁、陈其美等人加入以后,给南社带来了革命的气息,当时正是反清起义的1911年和民国初年。

1911—1912年柳亚子在上海是个活跃的报人,编辑几种支持革命的报纸,例如《笔铁报》,《天铎报》、《民声日报》、《太平洋报》。他还在南京孙逸仙办公室担任短期的秘书之职,但不久离职回上海继续些事报业。他在报刊上发表文章,反对革命者同袁世凯进行和平谈判。1912年2月袁世凯就任大总统后,柳亚子厌倦政治活动,回到吴江县。

此外数年,柳亚子从事文学活动,撰写诗文并编订南社同人的著述。南社同人毎半年在上海聚会一次,经常刊印社友诗文新作。1910年一1923年间,先后出版了诗文集二十二种,二十三册,不包括1917年出版的一本小说集。在此期间,柳亚子还在吴江县收集了当地很多诗文,编成一个集子,几百种珍本和手稿需要一一誊写保存,柳亚子本人也亲笔誊写了好几种。

南社存在的十四年间,柳亚子作为南社的领袖,结交了国内不少作家和政界人物。南社最后解体,表面上的原因似乎是由于对唐、宋诗体孰忧孰劣的不同评价。以柳亚子为代表的一派倾慕唐代诗体,对近代作家中,推崇十九世纪的诗人和革新派龚自珍,而陈三立、郑孝胥等人为代表的另一派则服鷹“同光体”(1862—1902年)。“同光体”就其渊源来说是南宋诗派。南社内部争论和解体的真正原因,却在于柳亚子日渐感觉到传统的中国文学语言不足以表达近代中国的思想和感情。他十分赞同李大钊、胡适领导采用白话文的新文化运动。柳亚子自己也开始用白语写文章,虽然也承认他用白话写诗没有什么成就。在文学观点上的这种变化,终于使他辞离了南社。1923年,他又组织了一个“新南社”,目的在于通过介绍世界新思潮和重新评价中国古典文学来创立一种新文学,但是,“新南社”的成就不大。

柳亚子被华南的国民党和革命力量的新的崛起所吸引,那正是1924年国民党改组和在广州建立新政权的时期。在此之前他在自己的家乡积扱发展国民党的地下组织,这时就被推举为国民党江苏省执行委员会委员和宣传部长,1926年他去广州出席的国民党第二次全国代表大会,当选为中央监察委员。不久,当时广州军事头领蒋介石对国民党内左派和右派斗争所采取的态度,使柳亚子深为不满。柳亚子是亲近廖仲恺的分子,他竭力主张坚持孙逸仙联共联俄的政策。

柳亚子由广州回到吴江县,不久因孙传芳统治了苏浙而去上海避居几个月。1927年5月,柳亚子因蒋介石清除共产党人和国民党左派而被迫逃到日本。在日本流亡将近一年后,他于1928年4月从日本回上海,他拒绝参加新成立的南京国民政府,因为他认为这个新的国民政府所执行的政策是和孙逸仙的遗嘱背道而驰的,然而,在1931年国民党第四次全国代表大会中,柳亚子还是被选为中央监察委员。1932年上海市效府任命柳亚子为“通志馆”馆长。此后几年中,在柳亚子的主持下,出版了好几种年鉴、上海地方史资料。

1937年,年中中日战争爆发,中止了他的这些工作。日本佔领时期,他在上海住了近三年。他断绝一切政治交往,过着隐居生活,专心致志收集南明遗族于十七世纪下半叶反抗清朝征服者的历史资料。1940年4月,汪精卫汉奸政府在南京登场。柳亚子耽心被这个曾经一度是国民党左派、又一度加入过南社的汪精卫胁迫参加伪政府,所以在12月仓促离开上海去香港。1941年1月皖南事变发生时,柳亚子从香港发电报到重庆,斥责国民党破坏抗日统一战线的行为。他因此被开除出国民党。

1941年12月,日军佔领香港,柳亚子遗弃了辛勤积累的南明史料逃往内地,他经过粤南海丰游击区于1942年6月到达桂林,此后二年,他专心致力于文学活动,写了不少作品。1944年他去重庆再次投身政治活动。1945年加入民主同盟,又同别人一起创建“三民主义同志会”,并从1946年到1948年担任该会主席。

1945年底,国共两党政治上的冲突扩展成为内战,柳亚子当时回到上海,他发现自己作为民盟的一员在上海是不安全的,1947年又去香港参加了一个反蒋组织。1948年1月参加以李济琛为主席的国民党革命委员会,参加这个组织的除柳亚子之外,还有一些知名人士如:冯玉祥、何香凝、谭平山。1949年柳亚子到北京,在那里度过了他的晚年。中央人民政府成立后,1949—1954年他曾参加政府委员会,1964—1958年任全国人民代表大会常委、国务院文教委员会委员。因为年老多病,他很少参加公众活动,也很少著述,甚至与家人也很少通信。1958年6月因肺炎逝世,终年七十一岁。

柳亚子的主要贡献在文学,特别是诗词方面。他是中国古体诗词最后的杰出人物之一,并且是同时代中最多产的作家之一。他只是偶尔编印了几本自己的作品,主要的有1927—1928写作的《乘桴集》,1947年写作的《怀旧集》。他的大多数早期诗词文章,可以从南社的大约二十本集子中找到。他的两个女儿柳无非、柳无垢编印了《柳亚子诗词选》于1959年在北京出版。柳亚子是一位热诚的目录学家,书画收藏家,他孜孜不倦地编印了他的友人们的文学遗作,著名的有1928年编印的苏曼殊全集。柳亚子还有与毛泽东的诗文友谊,两人曾几次以旧体诗相互唱和,而且看来与毛的几首著名的诗词的形成直接关系,包括《雪——沁园春》,在这首词里,毛泽东用喑示的手法把自己与中国历史上几个主要人物作了有利于自己的对比。

柳亚子不善于料理家务,全靠他夫人郑佩宜的照料。他们是于1906年结婚的。在漫长的岁月里,郑佩宜一直陪伴柳亚子,和他共同奔波,同经患难。柳亚子的儿子柳无忌(1907—)毕业于清华大学,于1931年取得耶鲁大学英文专业的哲学博士学位。以后在印第安那大学教中国文学。