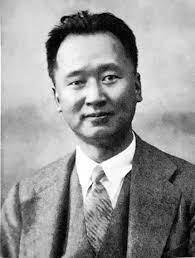

Li Chi (1896-), archaeologist who became head of the archaeology' section of the Academia Sinica"s institute of history and philology in 1928 and director of that institute in Taiwan in 1955. He was best known to Westerners for his direction of the excavations at Anyang. A native of Chunghsiang, Hupeh, Li Chi was born into a scholarly family. His father, Li Hsün-fu, served in the Ch'ing government in Peking, where Li Chi received his childhood education. When the Tsinghua Academy was established in 1911 to prepare students for higher education in the United States on Boxer Indemnity Fund scholarships, Li took and passed its first entrance examination. After being graduated in 1918 he went to the United States, where he studied psychology and sociology at Clark University in Alassachusetts. He received the B.A. in 1919 and the ^LA. in 1920.

In the fall of 1920 Li began graduate work at Harvard in anthropology and archaeology. He received the Ph.D. in 1923. His doctoral dissertation was The Formation of the Chinese People: An Anthropological Inquiry. An abridged Chinese translation by Lei Pao-hua appeared in the journal K'o-hsueh [science], in 1925. Li later expanded the dissertation, and it was published by the Harvard Universitv Press in 1928.

After returning to China in the autumn of 1923, Li accepted an appointment as lecturer at Xankai University in Tientsin. He soon met '. K. Ting Ting Wen-chiang, q.v.), who was then general manager of the Pei-p'iao Coal Company. Later, when Ting heard that a large number of ancient bronze vessels had been discovered in Hsincheng, Honan, he sent Li and a member of the China Geological Survey to investigate the site of discovery, but, because of the uncooperative attitude of the local populace and a rumor of banditry, nothing came of the effort.

In 1925 Tsinghua Academy was reorganized as a university. A research institute for Sinological studies was established with the aim of applying modern research methods to the study of traditional Chinese culture. Li was asked to join its faculty in company with such eminent scholars as Liang Ch'i-ch'ao, Wang Kuo-wei, and Chao Yuen-ren I'qq.v.). In the meantime, the Freer Art Gallery, through its representative Carl W. Bishop, had invited Li to join its field archaeology^ staff. Because of his obligation to Chang Po-ling (q.v.), the chancellor of Xankai University, Li found it difficult to decide which offer to accept. On the advice of '. K. Ting, Li accepted the Tsinghua appointment and advanced two conditions for participating in the Freer venture: that excavations must be done in cooperation with Chinese academic organizations and that all cultural relics must remain in China. Two months later, he received a letter from Carl Bishop which stated that the Freer Gallery would never ask a patriotic man to do what he did not want to do. Li was satisfied with the answer. Subsequently, an agreement was made between Bishop and the Tsinghua Research Institute by which the Freer Gallery would finance an expedition directed by Li and sponsored by the university. Li and Yuan Fu-li, a geologist, then undertook the Hsia-hsien expedition in Shansi. Excavation was begun in the spring of 1926 at the village of Hsi-yin-ts'un, and numerous prehistoric painted potsherds and some silkworm cocoons were found. The result of this expedition was reported in Li's Hsi-jints'un shih-ch'ien ti i-ts'un [prehistoric remains at Hsi-yin-ts'un], published by Tsinghua University in 1929. In 1928 the research institute at Tsinghua was discontinued. Li then went briefly to the United States to discuss with officials of the Freer Gallery the possibility of continuing his excavating work. The Freer Gallery agreed to give Li complete freedom to collaborate with any Chinese academic institution he chose. When the institute of history and philology of the Academia Sinica was formally established in Canton in November 1928 under the direction of Fu Ssu-nien (q.v.), Fu wired Li Chi asking him to head the archaeology section of the institute. In December, Li met Fu in Canton, where the two men came to an understanding on Li's status with the Academia Sinica and with the Freer Gallery. Li was to undertake a planned excavation of the Yin site at Anyang, Honan, for both the Academia Sinica and the Freer Gallery, with the latter providing the financial support. Soon after, in the spring of 1929, the institute of history and philology was transferred to Peiping; Li remained in Peiping until 1934.

Previously, in October 1928, before Li had been appointed to his new post, Fu Ssu-nien had sent Tung Tso-pin (q.v.), a member of the institute, to make a preliminary survey of the Anyang site. The excavation under Li's direction which began on 7 March and which lasted until 10 May 1929, was the second of a series of fifteen digs undertaken at Anyang prior to the Japanese invasion. A great quantity of potsherds, some bronzes, and 684 inscribed oracle bones and tortoise shells were uncovered. Work at the site was interrupted by civil war between Feng Yü-hsiang (q.v.) and Chiang Kai-shek, but excavations were resumed in the autumn. From 7 October to 12 December an unprecedented number of inscribed oracle bones and shells, some pottery and bronze vessels, and two inscribed oracle bones and skulls were unearthed. A unique fragment of painted pottery was also discovered at the site. This discovery created the possibility of identifying for the first time the chronological relationship between the prehistoric painted pottery culture of Yangshao, discovered in 1921 by J. G. Andersson, a Swedish geologist, and the historic Shang- Yin culture.

Disputes with the Honan provincial authorities and unauthorized diggings ca^jed on under their auspices caused suspension c^l^^e Anyang excavations. Li tendered his resigiferlion to the Freer Gallery on 22 February 1 930. Thfe burden of the financial support for the operation was then assumed by the China Foundation for the Promotion of Education and Culture, which presented the institute with a chair in archaeology with an annual salary of 6,000 yuan for five years and an annual grant of 10,000 yuan for three years for field work to begin in 1931.

With the Anyang excavations halted and the financial question waiting to be settled, Li devoted his time to writing and editing the reports of the Anyang finds. In May, he went to Nanking to investigate the site of Six Dynasties tombs and then to Shantung province where Wu Chin-ting, an assistant at the institute, had discovered a black-pottery site at Ch'eng-tzu-yai in Lich'eng. Realizing the importance of the find, Li decided to start excavating there on 7 November 1930. After 30 days of digging, the expedition confirmed the existence of a new culture complex, which Li designated the Lungshan culture in honor of the township in which Ch'eng-tzu-yai is located.

The excavations at Anyang were resumed on 21 March 1931, with the' support of the Honan government, and lasted until 1 1 May. Li was joined by tw^o other trained archaeologists, Liang Ssu-yung (q.v.) and Kuo Pao-chun. At Houkang, the fifth series of excavations, from 7 November to 9 December, unearthed Yin, Lungshan, and Yangshao strata in clear stratigraphic sequence. This was the first time that strata representing these three culture complexes had been found in a single site. The Japanese invasion of Manchuria on 1 8 September 1931 aroused Li's patriotism. A group of scholars, including Fu Ssu-nien and T. F. Tsiang (Chiang T'ing-fu, q.v.), had written Tung-pei shih-kang [outline history of the Northeast], an historical account of China's relationship with the northeastern provinces, designed to refute Japanese propaganda saying that Manchuria had never been a part of China. Li took time out from his archaeological work to abridge and translate this work into English. It was published in Peiping in 1932 as A/a«churia in History : A Summary. The deepening national crisis lent a sense of urgency to the task of completing the Anyang excavations. The sixth series of excavations was carried out from 12 April to 31 May 1932, the seventh from 19 October to 15 December 1932, and the eighth from 20 October to 25 December 1933. In 1934 the institute of history and philology was moved from Peiping to Nanking. The ninth series of excavations, from 9 March to 31 May, shifted the base of operations from Hsiao-t'un on the south bank of the Huai River to Hou-chia-chuang on the north bank. In the tenth series, from 3 October to 29 December, four large tombs were opened, in which more than a thousand stone implements were discovered. Li agreed with Liang Ssuyung, who was the field director, that Hou-chiachuang was undoubtedly the burial ground of the Yin capital unearthed at Hsiao-t'un. Since it was known that the Yin people paid much attention to the dead, it was decided that a largescale excavation of the new site was justified. li By that time Li had succeeded Fu Ssu-nien as the director of the preparatory office of National Central Museum, which was organized in April 1933 with the support of the British Boxer Indemnity Fund. V. K. Ting, thcdirector general of the Academia Sinica, was a member of the museum's board of directors. Since additional financial support was needed to finance the Hou-chia-chuang excavation, Li proposed that the museum assume part of the expenses. Ting readily gave his consent. In March 1935 work began on the burial site. A great variety of bronze, jade, ivory, and pottery remains were uncovered before digging ceased on 15 June. After a summer recess, the excavation was resumed with a force of 500 workmen. In the period from 5 September to 16 December, 8 large tombs and 785 small tombs were opened. Beginning with the thirteenth series of excavations, from 18 March to 24 June 1936, the operation was shifted back to the Hsiao-t'un site, where an unprecedented number ofinscribed oracle bones and tortoise shells were found. The Anyang and Lungshan discoveries gained world-wide attention through the reports issued by the institute and the writings of such noted scholars as Paul Pelliot, Bernard Karlgren, and W. P. Yetts. In the spring of 1936 some of the Anyang bronzes were displayed at the Chinese Art Exhibition held in London. That winter, Li was invited by the English Association of Universities and the Swedish heir apparent, later King Gustav T, to lecture at London and Stockholm.

The fifteenth series of excavations were undertaken from 16 March to 10 June 1937. Several weeks later, the Sino-Japanese war broke out. Li, who had just returned from Europe, supervised the removal of all the records and remains of the Anyang excavations from Nanking to Changsha, Hunan, where the institute of history and philology found a temporary home. When the Japanese advanced toward Hankow, the institute was evacuated farther inland to Kunming, Yunnan. In 1938, in recognition of his contributions to the development of archaeology in China, the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland elected Li an Honorary Fellow.

Li soon resumed field investigations. Expeditions were dispatched to Shensi, and to Tali and Kunming in Yunnan. In 1939 the institute was moved to Lichuang, a village in Nanch'i, Szechwan, where it remained until the end of the war. In the spring of 1946 the institute returned to Nanking. Soon afterwards, Li was appointed a member of the Chinese delegation stationed in occupied Japan. His task was to trace and recover cultural objects pillaged from China by Japanese soldiers and civilians during the war. In March 1948 Li Chi was among the 81 scientists and scholars elected to the Academia Sinica. These men were to be responsible for the direction of the scientific development of postwar China. Liang Ssu-yung, Tung Tso-pin, and Kuo Mo-jo (q.v.) were also elected to represent the field of archaeology.

By the winter of 1948 the tide of civil war was turning against the National Government. The Academia Sinica had to be evacuated to Taiwan. Li aided in removing the art treasures and archaeological specimens of the institute of history and philology, the Central Museum, and the Palace Museum from the mainland to Taiwan. In February 1949 he was appointed professor of history at National Taiwan University. In August, he became the chairman of the university's department of archaeology and anthropology.

Li led a Chinese delegation to the Eighth Pacific Science Conference and the Fourth Far Eastern Prehistory Conference held in the Philippines in 1953. He accepted a Rockefeller grant in 1954 to lecture at the Escuela Nacional de Antropologia e Historia in Mexico. In 1955 the University of Washington at Seattle invited him to lecture on ancient Chinese culture. The three lectures he gave there were published in 1957 as The Beginnings of Chinese Civilization. After returning to Taipei in the summer of 1955, Li was appointed director of the institute of history and philology. He left Taiwan for the United States on 20 October 1959 to do research and lecture at Harvard. In June 1960 he visited the Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., and later, the Toronto University Museum in Canada to advise on the display of their collections of ancient Chinese artifacts. In July, he attended the Sino- American Conference on Intellectual Cooperation held at Seattle, Washington. He then returned to Taiwan, arriving there on 3 September. As an advocate of new methodology Li Chi succeeded through his writings and field work in making systematic excavation, stratigraphy, and typology essential to the scientific study of China's past history. He demonstrated that modern archaeology and the traditional study of ancient artifacts enhance each other. In this respect the An-yang fa-chueh pao-kao [report on the An-yang excavations] for 1928 edited by Li is epoch-making. Under his leadership Chinese archaeologists, with limited financial backing and working in a time of political turmoil, carried out significant excavations. Many leading Chinese archaeologists, such as Yin Ta, Hsia Nai, Yin Huang-chang, Shih Chang-yu, and Kao Chu-hsun received their practical training under Li.

As a student of China's ancient history Li wrote the pioneering study of the formation of the Chinese people, contributed significant studies of Shang artifacts, and formulated a precise and workable terminology for the description of ancient artifacts. His interpretations of the ancient cultures of north China, based on his intensive knowledge of many prehistoric and historic sites and collections as well as his wide acquaintance of archaeological developments in other parts of the world, greatly increased understanding of a still dimly known period of China's past. In these areas his most significant publications were The Formation of the Chinese People, Hsi-jin-ts'un shih-ch'ien ti i-ts'un, and Ch'eng-tzu-yai (1934), in which Li hypothesized a Lungshan culture complex extending over eastern China during the neolithic period and indicated its relationship to the civilization of Shang; the An-yang fa-chueh pai-kao for 192933, also edited by Li; "Yin-ch'ü t'ung-ch'i wuchung chi ch'i hsiang-kuan wen-t'i" [five bronze objects from Anyang and problems related to them], an article of 1933; and "Chi Hsiao-t'un ch'u-t'u chi ch'ing-t'ung-ch'i" [Hsiao-t'un and the bronzes discovered there], an article which appeared in Chung-kuo k'ao-ku hsueh-pao [Chinese archaeolog'] in 1948-49 and which established a precise and well-organized terminology for bronzes and the details of their decor.

李济

字:济之

李济(1896—1979),考古学家,1928年任中央研究院历史语言研究所考古组主任,1955年在台湾任该所所长,他在安阳的发掘工作在西方人士中负有盛名。

李济,湖北钟祥人,出身于诗书之家,他父亲李巽甫在北京清政府供职,李济在北京上学。1911年美国退回庚子赔款创办清华学堂派学生去美国深造,李济考取该校,1918年毕业后去美国,在马萨诸塞州克拉克大学习心理学、社

会学,1919年获学士学位,1920年获硕士学位。

1920年秋,李济进哈佛大学研究院研读人类学,考古学,1923年获得博士学位。他的博土论文《中国民族的形成:一项人类学调查》,此文由雷葆华节译在1925年的《科学》杂志上发表。李济将此文补充扩大后,又于1928年在哈

佛大学出版社出版。

李济于1923年秋回国后,在天津南开大学当讲师,他遇见北票煤矿公司经理丁文江。丁文江听说河南新郑发现大批古代青铜器,派李济和一名地质调查社的人员前去现场考查,但当地群众未能合作又谣传有匪患,因此未有成果。

1925年,清华学堂改为大学,并成立国学研究院,运用近代方法研究中国传统文化。李济和其他一些知名学者如梁启超,王国维、赵元任被聘参加。此时,美国弗里尔艺术馆代表毕晓普邀请李济参加该馆的实地考古团,当时,他已应南开大学张伯苓之聘,未能决定去就。后经丁文江之劝,受清华之聘,同时又以如下两个先决条件而参加弗里尔艺术馆的工作:发掘工作必须与中国学术单位合作,发掘所获文物必须留归中国。两个月后,毕晓普复信说,弗里尔

艺术馆从来不会让一个爱国者干他不愿干的事。李济对此答复表示满意,毕修普就与清华研究院签订了一个合同,由弗里尔艺术馆出经费,进行一项由李济领导和清华主办的发掘工作。于是李济和地质学家袁复礼从事了山西夏县的考

察,1926年春在西阴村开始发掘,发现了大量的史前彩色陶器碎片和一些蚕茧。这次发掘报告发表在1927年清华大学出版的《西阴村史前的遗存》。

1928年清华研究所停办。李济曾短期去美国与弗里尔艺术馆人员商谈继续发掘的工作。该馆同意由李济选择国内学术机构进行合作。1928年11月,中央研究院历史语言研究所由傅斯年主持在广州正式成立,傅斯年电请李济担任考

古主任,12月,傅、李在广州会面,双方就李济在中央研究院和在弗里尔艺术馆的地位达成协议。李济将为中央研究院,弗里艺术馆担任安阳殷墟的发掘土作,经费由后者提供。1929年春,历史语言研究所迁往北平,李济在北平一直住到1934年。

i928年10月,李济在任此新职之前,傅斯年曾派该所的董作宾对安阳殷墟作初步调査。在李济领导下进行了自1929年3月7日开始到5月10日的发掘工作。这是日本侵华前第二次在安阳进行的一批十五处挖掘。发掘了大批陶片,一些青铜器及684件刻有卜辞的甲骨。在冯玉祥蒋介石打仗时,发掘工作曾一度中断,秋季,又行恢复。从10月7日起到12月12日,出土了大量的甲骨片,陶器,青钢器和两具刻有卜辞的骨骼和头盖骨,并且还发现了罕见的彩陶。这个发现第一次确定了瑞典地质学家安德生发现的史前仰韶彩陶文化与股商文化的年代关系。

安阳的发掘因与河南省尚局和他们纵容下的私自挖掘发生争执,发掘工作陷于停顿。1930年2月22日,李济向弗罗尔艺术馆辞职。这项工作的经费由中华教育文化基金负担,该所给历史语言研究所从1931年开始提供一个年薪六千

元为期五年的职位,和为期三年每年一万元的实地工作经费。

随着安阳发掘的停顿,经费问题尚待解决,李济致力于编写安阳的发掘报告。5月,他去南京考査六朝墓葬,又去山东与该所一名助手吴金鼎在历城城子崖发现黑陶。了解到这一发现的重要性,李济决定于1930年11月7日开始发掘。经过三十日的挖掘,考古队证实了一种新的文化综合体的存在,李济将这种文化定名为龙山文化以纪念城子崖所在的地区。

1931年3月21日到5月11日安阳的发掘得到河南省当局的支持又恢复了,李济又得到两名有经验的考古学家梁思永、郭宝钧参加。11月7日到12月9日在后冈的第十五批发掘,发现了小屯、龙山、仰韶文化的分明层次。这是第一次三种文化的综合体发现于同一地点。

九一八事变,日军进犯东北,激起了李济的爱国情绪。一批学者如傅斯年,蒋廷黻等人编写了一本《东北史纲》,史地论证了东北与本部的联系,驳斥日本认为满洲从来不是中国的一部分的宣传。李济将此书节要译成英文,1932

年在北平出版,书名《从历史看满洲》。

民族危难的加深,完成安阳的发掘工作十分急迫。第六批发掘在1932年4月2日到5月31日进行,第七批于1932年10月19日到12月15日进行,第八批于1933年10月20日到12月25日进行。1934年,历史语言研究所由北平迁往南京。3月9

日到5月31日进行的第九批发掘工作基地由洹水南岸的小屯迁到北岸的侯家庄第十批由10月3日到12月29日发掘出四个大墓葬,出土一千多件石器。李济同意现场负责人梁思永的意见,认为侯家庄无疑是掘出的殷代都城小屯的墓葬地。由于殷人以重视死后墓葬而闻名,故断定对新现场的发掘是正确的。

李济继傅斯年任国立中央博物馆筹备处主任,该馆系由英国退回的庚款于1933年4月成立的。中央研究院院长丁文江是该馆理事。侯家庄的发掘追加经费,李济建议由博物馆提供一部份,丁文江立即同意。1935年3月,发掘工作

在墓葬地开始进行。在6月15日挖掘停止以前,出土了多种多样的青钢、玉象牙和陶器遗物。暑期休整后,用了五百名工人进行复原工作。在9月5日到12月16日期间,发掘出大型墓葬八处,小型墓葬785处。1936年3月18日到6月

24日第十三批发掘又转移回小屯,发现了大董带卜辞的甲骨。

通过研究所的发掘报告和著名学者伯希和、高本汉、颜慈的文章,安阳和龙山的发现获得世界的注意。1936年春,一些安阳青铜器在伦敦中国美术展览会中展出。是年冬,李应英国大学联合会和瑞典王储(后来的古斯泰夫四世)

之邀请,在伦敦和斯德哥尔摩讲学。

第十五批发掘进行于1937年3月16日到6月10日。数周后,中日战争爆发。李济方从欧洲回国,负责把安阳发掘的记录和文物由南京迁往长沙,该地为历史语言所临时所在地。日军入侵汉口,历史语言所迁往云南昆明。1938年,为

了李济在考古学发展上的贡献,英国皇家考古学会选他为名誉会员。

李济重又开始发掘工作,派出考古队到陕西、云南大理。1939年,历史语言所迁往四川南溪李庄,在那里留到战争结束为止。1946年春,历史语言所迁回南京,不久,李济被任命为驻在日本的中国代表团成员。他的任务是清査并

找回为日本军民在战时劫走的中国文物。1948年,李济是当选为中央研究院院士的八十名科学家及学者之一。这些人负责筹划战后的科学研究工作。梁思永,董作宾、郭沫若被选为考古学方面的负责人。

1948年冬,内战发展不利于国民政府,中央研究院迁往台湾。李济协助把历史语言所,中央博物馆,故宫博物院的艺术珍品和考古发掘文物从大陆迁到台湾。1949年2月任国立台湾大学历史系教授,8月任该校考古学及人类学系主

任。

李济率代表团出席1953年在菲律宾召开的第八届太平洋科学会议和第四届远东史前史会议,1953年获得洛氏基金捐款去墨西哥国立人类学历史学大学讲学,1955年西雅图华盛顿大学请他去做古代中国文化的讲学,他在那里的三次

讲演,于1957年以《中国文化始源》之名出版。

1955年夏,李济回台北后任历史语言研究所所长,1959年10月20日离台湾去美国进行研究讲学。他在1960年6月去华盛顿市的自然史博物馆访问,后又去加拿大多伦多大学博物馆请他去鉴定所收藏的有关中国古代文物及其陈列加

以指点。7月,出席华盛顿州西雅图举行的中美学术合作会议,然后于9月3日回到台湾。

作为一个新方法的提倡者,李济通过他的著作和实地工作使系统的发掘、地型学和类型学对中国过去历史的研究有重要作用,获得成果。他阐明近代考古学和古代文物的传统研究是相辅相成的。在这一方面,他在1928年编写的《安

阳发掘报告》是划时代的。在李济的领导下,中国的考古学家,在经费短缺,时局不稳的情况下进行了有重大意义的发掘工作,在李济的实践训练培养下,出现了一批第一流的考古学家如尹达、夏鼎、尹焕璋、石璋如、高去寻等人。

作为一个中国古代史的学者,李济写出了对中华民族形成的首创研究,对殷代文物的研究做出了重要贡献,并对说明古代文物订出了确切适当的名称。由于他对史前及历史遗址和收藏品的深邃知识,以及对世界各地考古学发展的

广泛了解,李济对华北古代文化的解释大大提高了人们对中国过去一段仍然模糊不清的历史的认识。这方面的重要著作,有他在1934年发表的《中华民族的形成:西阴村史前的遗存》、《城子崖》。在这些著作中,李济推定龙山文化综合体在新石器时代已扩展到华东,并说明其与殷代文化的关系。李济编写的1929—1933年《安阳发掘报告》;1933年发表的论文《殷墟铜器五种及其相关问题》;1948—1949年在《中国考古学报》上发表的《记小屯出土之青铜器》,在这篇文章中他给青铜器及其花纹作了确切恰当的订名。