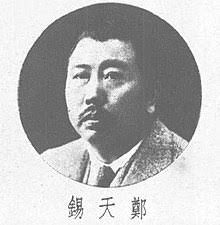

Cheng T'ien-hsi (10 July 1884-), known as F. T. Cheng, the first Chinese to receive the LL.D. degree in England, became vice minister of justice at Nanking (1931-34) and a judge of the Permanent Court of International Justice at The Hague ( 1 936-46) . From 1 946 to 1 950 he was ambassador to the Court of St. James's. In 1 950 he was granted rights of residence in England. Although F. T. Cheng was a native of Hsiangshan (Chungshan), Kwangtung, he was born at Mamoi, near Foochow. A few days after his birth a French naval flotilla attacked Foochow. The family fled to Hong Kong, where Cheng's father, Cheng Ching-nan, became a buyer in a British firm. Since Cheng Ching-nan hoped to make his son a scholar, he sent F. T. Cheng back to his native district at the age of six to begin his traditional education. At the age of eight, Cheng rejoined his family in Hong Kong where, after a year in a private school, he studied with a tutor. After working under the tutor for a year, Cheng went back to the village school in Kwangtung because there was an epidemic in Hong Kong. In 1894 he returned to Hong Kong, entered a new Chinese school, and began to learn English. In 1896, during another epidemic, his father died. Cheng then abandoned his idea of becoming a classical scholar and decided to take up a career in business to support his mother. As a result of that decision he began serious study of English and mathematics under an uncle who had been a student at the Royal Naval College at Greenwich, England. He made progress, and his uncle's influence awakened a desire in Cheng to go to England. After a year with his uncle, Cheng entered Queen's College, the government-run English school for Chinese boys in Hong Kong. He boarded in a provisions store with which his father had once had business connections. He slept on the counter in traditional apprentice style and helped in the shop in out-of-school hours. He remained at Queen's College for only one year, until 1898. Then another epidemic broke out in Hong Kong, and Cheng returned to his native village in Hsiang-shan on his mother's request. There he continued to study English on his own. After returning to Hong Kong, he became associated with Cheng Kuan-kung, a fellow-clansman whom he had known since childhood. Cheng Kuan-kung had recently returned from study in Japan and worked on the Chung-kuo jih-pao [China daily news] , the anti- Manchu revolutionary paper established in Hong Kong in 1899. Cheng Kuan-kung later resigned and established his own newspapers. Although F. T. Cheng took an active interest in these enterprises and was exposed to the political ideas of the period, he did not become involved in the revolutionary movement. He went into business, first as a shareholder in a provisions firm, which failed because of the manager's incompetent accounting, and then as a sales agent for a sewing-machine company. From that modest beginning he rose to become an agent for several European firms. He then established his own export business, located on Des Voeux Road in Hong Kong, where he dealt in bristles, rice, fireworks, and human hair. Cheng's credit rating was good, and the firm prospered. Cheng married, and he and his wife had a daughter.

In 1907 Cheng left his family at Mamoi and set off for England to realize his dream of studying law. In London he spent two years with a private tutor, a Cambridge graduate named A. E. Williams, preparing for the London University matriculation. He formed a close friendship with Williams, who taught him much about English life and who introduced him to Arthur Machen, an author and a regular contributor to the London Evening News. Machen gave him Boswell's Life of Johnson to read ; it became one of Cheng's favorite books. Cheng took his LL.B. degree with honors in 1912, and was called to the bar at the Middle Temple in April 1913. He then returned to China for a brief visit with his family. He was offered the post of procurator general in the high court at Canton, but refused the appointment because of his determination to return to London to obtain his doctorate. He did return to England in 1914, this time taking his wife with him, and began work on his thesis, "Rules of Private International Law Determining Capacity to Contract." In August 1915 he published an article entitled "A Chinese View of the War" in the National Review. The article drew favorable comment from several other journals. In 1916 he received his LL.D. He was the first Chinese student to achieve that distinction, and the Chinese minister to England, Alfred Sze (Shih Chao-chi,q.v.) gave a special dinner in his honor. After receiving his doctorate, Cheng remained in London for another year to learn the practical side of the law. On the recommendation of Sir John Macdonnell, he entered the chambers of Bromley Eames and, when Eames died, the chambers of Theobald Mathews. During this period Cheng attended the Quain lectures on comparative law and public international law given by Sir John Macdonnell and shared the Quain prize for an essay entitled "What is the Liability of Belligerents for Injuries Caused to Neutrals by Reprisals?" In January 1917 Cheng left England with his wife and newborn second daughter to return to China. They planned to travel by way of Siberia because of the war; Alfred Sze had made Cheng a diplomatic courier to facilitate customs procedure. Boarding the Newcastle train at King's Cross to begin his journey, Cheng met Wang Ching-wei (q.v.), who was returning to China by the same route. When they finally arrived in Peking at the end of the long trip, Wang Ching-wei introduced Cheng to Hu Hanmin, the former T'ung-meng-hui leader and close associate of Sun Yat-sen, and to Wang Ch'ung-hui and Lo Wen-kan (qq.v.), respectively chairman and vice chairman of the law codification commission.

Cheng went to Hong Kong and was admitted to the bar there in May 1917. The following month he was retained as counsel for the defense in a murder case and was complimented by the court for his handling of the case. His prospects for a successful law career in Hong Kong seemed good. But, acquaintances in Peking, specifically Wang Ch'ung-hui and Lo Wen-kan, urged him to return to Peking, where there was urgent need for Western-trained legal experts. He went north to the Chinese capital to join the judicial branch of the government.

Cheng received a minor post in the ministry of justice as supervisor in charge of translation of Chinese law into English. He translated most of the material himself and put into English virtually all the new laws of the republic, including the provisional criminal code, the draft code of criminal procedure, the draft civil code, the draft code of civil procedure, the prize law, the prize court judgments, and the Supreme Court decisions. Soon, Cheng was transferred from the ministry of justice to the law codification commission. In 1919 he was made a judge of the Supreme Court, but at the end of 1 920 he returned to his position with the law codification commission. He was attached to the Chinese delegation at the Washington Conference of 1921-22. Afterwards, an international commission on extraterritoriality was established to examine the Chinese judicial system with a view to abolition of extraterritorial jurisdiction, and Cheng became a deputy delegate and an adviser to that commission. In 1922 he was appointed chief compiler of the law codification commission; two years later, following political changes in Peking, he resigned. He also held other posts in Peking: examiner for judicial candidates, tutor of the judicial academy, and professor of law at Peking University. In 1927, after the arrival of the Nationalist forces in the Yangtze valley, Cheng moved his family to Shanghai and established a private law practice, which soon prospered. He declined the post of president of the high court in the government. Instead, he accepted a special partnership in a well-known firm of foreign lawyers. He also became a professor at the law school of Soochow University. His intentions to remain apart from official life were soon overcome. In 1932, on the recommendation and persuasion of Wang Ching-wei, he became vice minister of justice at Nanking, under Lo Wenkan. Cheng held that post until 1934 and served as acting minister for a brief period in Lo's absence. During this period Cheng's mother died, an occasion which he described as being the saddest day of his life.

When Lo Wen-kan resigned as minister of justice in October 1934, Cheng also left office, but agreed to continue to serve as adviser to the ministries of justice and foreign affairs. He planned to return to private law practice in Shanghai. In 1935, however, Wang Shih-chieh (q.v.), who was then minister of education, invited Cheng to go to London to head a special cultural mission in charge of the art treasures being sent to the International Exhibition of Chinese art at Burlington House. That exhibition turned out to be one of the most successful ever held in London. During the period of its display Cheng delivered a series of three lectures on Chinese culture; these were published in 1936 under the title Civilization and the Art of China, with a prefatory note by Cheng's old friend Arthur Machen. He was also invited by Queen Mary to inspect her palace collection of Chinese art objects. Although he had no great knowledge of Chinese art, a fact which he readily admitted, F. T. Cheng contributed substantially to the success of the exhibition because he was a witty public speaker and knew England and the English well. He discharged the mission with great personal satisfaction, since it permitted him to renew old contacts in a country to which he was strongly attached and in a capacity free of political complications. The Chinese art exhibition ended in the spring of 1936, and the art treasures were shipped to China aboard the P. and O. liner Rampura. When the vessel ran aground at Gibraltar in April, Cheng had many anxious moments in London, where he was winding up the exhibition's affairs. Fortunately, the vessel was refloated safely, and Cheng was able to return triumphant from his London mission. Shortly after his return from London, Cheng was appointed a judge of the Permanent Court of International Justice at The Hague, succeeding Wang Ch'ung-hui. With the German occupation of the Netherlands in 1940, Cheng moved with the court to Switzerland and remained there until the end of the war. He continued in his post until January 1946, and was then made a member of the board of liquidation of the League of Nations at Geneva.

On his return to China, Cheng was appointed ambassador to Great Britain. He took up his duties at London in August 1946 and, in that familiar milieu, spared no effort to promote cultural and economic relations between China and England. He continued in that post until the British government recognized the Central People's Government at Peking in January 1950. At that time Cheng was granted rights of residence in England.

After 1950 Cheng resided in New York, where he was an adviser to the Wah Chang Corporation, and in London. He also was adviser to the Judicial Yuan of the National Government at Taipei and a member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague.

F. T. Cheng's great diligence contributed much to his successful career. He has been respected by both Chinese and Westerners for his personal conduct and for his independence from political affiliations. As ambassador to Great Britain, he won the affection of royalty and commoner alike as a Chinese gentleman. Cheng had a strong sense of filial devotion and respect for Confucian principles. He also was well acquainted with such Western works as those of Shakespeare and Samuel Johnson, from which he loved to quote. Cheng was a lawyer of distinction ; a diplomat who discharged his duties with skill and tact; and an urbane public figure. A sociable man in private life, he liked good food and wine and considered dining to be an art essential to good living. Simplicity, not lavishness, marked his tastes.

Cheng wrote several books in English : China Moulded by Confucius, which was published in London in 1946; East and West: Episodes in a Sixty Years' Journey, which was published in London in 1951; and Musings of a Chinese Gourmet, which was published in London in 1955.

郑天锡

字:定茀

郑天锡(1884.7.10—),是在英国获得法学博士的第一个中国人,1931—34在南京任司法部次长,1936—46年任海牙国际常设法庭判事,1946—1950年任驻英大使。1950年取得在英的居住权。

郑天锡原籍广东香山,他本人生在福州附近的马尾,他出生后没有几天,法国舰艇袭击福州,他全家逃亡香港,父亲在一家英国商号当采购员。

他父亲郑锦南希望他儿子成为一个学者,六岁时送他回原籍受旧式教育,八岁时又去香港,在私立学校读书一年后,就随一名家庭教师读书。一年后,因香港流行疫病,他又回广东。1894年,他又去香港入华人学校习英语。1896年,香港又流行疫病他父亲因此致死。从此,郑天锡放弃了成为学者文人的打算而改习商务,瞻养母亲。经此改变,他在叔父教导下勤勉学习英语、数学,他叔父原是英国格林威治皇家海军学院的学员。郑天锡颇有进步,又在他叔父影响下盼望能到英国去。他在英国和叔父一起住了一年后,进入香港皇仁书院,这是英官方为香港的华人子弟而办的学校。他寄宿在他父亲曾有商业来往的一家伙食铺子里,以传统学徒式的生活,晚上睡在柜台上,课余帮助料理店务。

1898年他在皇仁书院只过了一年,那时香港又流行疫病,他母亲叫他回广东香山,他继续自习英语。他重回香港后遇到幼年伴侣同族人郑贯公,那时,郑贯公才从日本学习回来,在一家1899年香港创办的反满革命报纸《中国日报》工作,后来,他辞去《中国日报》自行办报。郑天锡虽然对此很有兴趣而且因此受到当时的那些政治观点的影响,但他未参与革命活动。

郑天锡经了商,起先是合股经营一家粮食行,因经营不善而遭失败。后来,又当了一家缝纫机行的经纪人。他从这平凡的起点,后来成了好几家欧洲商行的经理人。他在香港戴伏路开了一家出口商号,经销皮毛、大米、花炮、头发各色物品。郑天锡信用卓著,生意兴隆。那时郑天锡结了婚,生了一个女儿。

1907年,郑天锡一家迁离马尾去英国以实现他学习法律的理想。他在伦敦和一位教师剑桥毕业生威廉士相处二年,准备伦敦大学的入学考试。他和威廉士的交情很好,后者经常告诉他一些英国的人情风物,并介绍他认识了梅琴,他是一个作家,又是伦敦《晚报》的撰稿人。梅琴介绍郑天锡阅读博斯威尔的《约翰逊传记》,这成了郑天锡一本珍读的著作。

1912年,郑天锡取得法学士学位,1913年4月在中院开业。在此期间,他曾回国探亲,广州高等法院聘他为检察官,郑天锡因为要回英国取得博士学位未受聘,1914年,他携妻子回英国,撰写论文《条约行为在国际私法中的规定》。1915年在《全国评论》上发表论文《中国的战争观》,得到很多杂志的好评。1916年获得法学博士学位,他是第一个获得这学位的中国留学生,中国驻英公使施肇基为此举行特别宴会。

郑天锡取得博士学位后,又在伦敦居住了一年,以便取得实际经验。他经麦克唐纳介绍进了埃姆斯律师事务所,埃姆斯死后又进了马修斯律师事务所。在此期间,他在麦克唐纳的奎因讲座听课,学习比较法和国际公法。他写了一篇《交战国对受害中立国的责任问题》获得奎因奖金。

1917年1月,他携带妻子和初生的第二个女儿回国。因战争的关系,他们计划取道西伯利亚。施肇基使郑成为个外交信使,以简便海关手续。他在皇家道口登纽喀赛火车启程,遇到同路回国的汪精卫。他们经长途旅行后到达北京,汪精卫把郑天锡介绍给前同盟会领袖也是孙中山的知交胡汉民,又介绍给法律编纂委员会副主席王宠惠、罗文干。

1917年5月,郑天锡去香港开业。6月,他被聘为一件谋杀案辩护师,他对此案件的处理得到法庭好评。郑天锡在香港的律师行业看来很有前途。但是,他在北京的朋友,特别是王宠惠、罗文干,希望他回北京,因为极需要受过西方训练的法律专家。郑天锡回到北方,在政府的司法部门工作。

他在司法部的职位很低,负责监督将中国法律译成英文,他亲自翻译了不少,几乎全部的民国新法,其中有刑法,刑法程序草案、民法程序草案、惩奖法、惩奖条例和最高法院判例。

不久,郑天锡由司法部调到法制编纂委员会。1919年任大理院判事,1920年底又回法制编纂委员会。l921—22年随同中国代表团出席华盛顿会议,后来因各国准备取消在华治外法权成立国际治外法权委员会调查中国司法情况,郑天锡任该委员会副代表兼顾问。1922年任法律编纂委员会主任,两年后,因北京政局变化而辞职,但仍在北京另任他职:法官考审、法律学院教师、北京大学法学教授。

1927年,国民革命军到达长江流域,郑天锡迁居上海,设律师事务所,生意兴隆。他辞谢政府的高级法院院长之职,而与其他外国律师一起当了一家有名的商行的法律顾问。他曾任苏州东吴大学法学教授。他想置身于公共事务之外的打算很快就过去了。1932年,经汪精卫的推荐和劝请,任南京司法部次长,部长罗文干。他任此职直到1934年,在此期间罗文干不在职时曾短暂地任代理部长。这期间,他的母亲死去,他说这是他一生最悲痛的时期。

1934年10月,罗文干辞职,郑天锡亦离职,但仍同意在司法部和外交部任顾问。他准备回上海继续私人律师事务所的工作。1935年,教育部长王世杰,请郑天锡率领文化代表团去白金汉宫国际展览会展出中国艺术珍品,这是伦敦从未见过的一次最为成功的展览会。展出期间,郑天锡作了三次有关中国文化的讲演,1937年编成《中国的文化和艺术》一书出版,内有他的老朋友梅琴所写的序言。他又受到玛丽皇后的邀请,去欣赏英国皇宫收藏的中国艺术品。实际上,郑天锡本人也承认他对中国艺术并不内行,但他言谈富有智趣,又精通英语熟悉英国,所以使展览获得巨大成功。他完满地完成了他的使命,个人方面也极满意,因为有这次机会使他能重温对英国的深厚感情,又可以避开政治纠纷。

1936年春,展览会结束,中国艺术珍品由太古轮船公司“兰普拉”号运回中国。4月,该船在直布罗陀搁浅,郑天锡在伦敦十分焦急,因为在伦敦料理一切的是他。幸而该船浮出重航,郑天锡伦敦之行才能胜利结束。他从伦敦回国后不久,继王宠惠而任海牙国际常设法庭判事,1940年,德国占领荷兰,郑天锡随法庭移居瑞士,一直到战争结束,继续任判事到1946年1月。以后又任日内瓦国际联盟清偿局成员。

他回国后,被任命为驻英大使,1946年8月到职,他在这个熟悉的环境中,对改善中英的文化经济关系不遗余力。他任驻英大使之职,一直到英国政府于1950年1月承认北京的中华人民共和国,那时,他已获准在英国居留。

1950年后,他分别在纽约、伦敦居住。他在纽约任华成公司顾问,又是台北国民政府立法院顾问,海牙常设法庭裁决成员。

郑天锡事业上的成就得力于他的勤奋,中西人士对他个人品行和政治独立性表示尊崇。他任驻英大使时,赢得英国的贵族和平民的爱戴把他看作是一个中国的正人君子。他对儒家原则唯诚唯敬。他熟知一些西方作品诸如莎士比亚、约翰逊的作品而常加引用。郑天锡是一个杰出的律师、机智的外交家、城市名流人物。他好客又精于饮食,他认为饮食是美好生活中的重要艺术,朴素而不奢华,这是他的兴趣的特点。

郑天锡用英文写了几本书,1946年在伦敦出版《儒家塑造了中国》;1951年在伦敦出版《东方和西方:六十年经历中的奇遇》;1955年在伦敦出版《中国食品鉴赏者的怀想》。