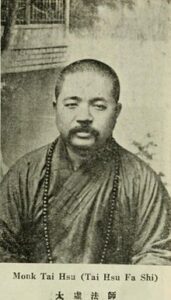

T'ai-hsu (8 January 1890-17 March 1947), Buddhist monk of the wei-shih [consciousnessonly] school who led a movement to reform and modernize his religion. He headed the Wu-ch'ang fo-hsüeh yuan [Wuchang Buddhist institute], edited the Hai-ch'ao-yin, and established such organizations as the World Buddhist Association.

Although his native place was in Ch'ungte, Chekiang, T'ai-hsu was born into a poor family in Haining. His father, a bricklayer, died when he was one year old, and his mother remarried when he was five. He spent his childhood in Haining under the care of a maternal grandmother and an uncle. T'ai-hsü received a primary education in the Chinese classics from his uncle, a village school teacher, and he often traveled with his grandmother when she made pilgrimages to Buddhist temples in the area.

At the age of 15, T'ai-hsü was compelled by straitened financial circumstances to go to work as a shop clerk. However, he soon left the job because he wished to become a Buddhist monk. A short time later, he entered the T'ien-t'ung temple near Ningpo, where, from 1906 to 1910, he received basic instruction in Buddhism. He became attracted to the teachings of the T'ient'ai and Hua-yen schools, and about 1908 he came to know monks who were sympathetic with reform efforts. At their urging, he began to read works by K'ang Yu-wei, Liang Ch'ich'ao, T'an Ssu-t'ung, Chang Ping-lin, Tsou Jung, and Yen Fu, as well as such revolutionary newspapers as the Min Pao [people's journal], which then was published secretly in Japan. In 1910 T'ai-hsü went to Nanking, where he studied under Yang Wen-hui (1837-1911; T. Jen-shan), a prominent Buddhist layman who was director of the Buddhist Press. In 1911 he went to Canton, where he was associated with anti-Manchu revolutionaries and developed an interest in anarchism and socialism after reading Chinese translations of works by Tolstoy, Bakunin, Proudhon, and Marx. He participated for a time in a discussion group on socialism and became convinced of the necessity for a social revolution in China.

T'ai-hsu's interest in socialist ideas affected his interpretation of Buddhism and soon led him to formulate plans for a new Buddhist movement in China. He contended that Buddhism and socialism were similar in that both advocated social equality and salvation for all. However, he felt that Buddhism in China had degenerated and had been unable to fulfill its aims because of the relaxation of Buddhist order. Monks had become ignorant, and Buddhist properties were monopolized by a few. Furthermore, the ancient Buddhist doctrines had become outmoded in the new social environment of twentieth-century China. T'ai-hsu believed that the scriptures needed to be redefined with reference to new currents of thought. Buddhism had become an object of popular hostility: temples had been destroyed, and Buddhist properties constantly faced threats of government confiscation. T'ai-hsu therefore aimed at a threefold reform movement : regeneration of the Buddhist clergy, rededication of Buddhist properties, and redefinition of Buddhist doctrines. About 1909 he helped to establish the Association for Monks' Education at Ningpo ; in 1910 he founded the Association for the Promotion of Buddhist Education at Canton. In 1912 T'ai-hsü participated in the formation of the Fo-chiao hsieh-chin hui [Buddhist association]. At the organization's first meeting in Chinkiang, he set forth his principles of religious reform. He believed that Buddhist land holdings were the common property of all followers of the religion and should be dedicated to the promotion of social welfare, particularly education. In a statement that aroused strong controversy, he advocated the adoption in religious communities of the principle that each person should be judged by his abilities and rewarded according to his work. Moreover, he argued for the redefinition of Buddhist doctrine because he believed Buddhism to be a religion for this world. The evolutionary process of religion corresponds with that of political life, and both religion and government should have the same goal: a grand union in which people work according to their abilities and receive according to their needs. In 1913 he wrote: "The evolutionary process of politics is from tribe to monarchy, from monarchy to republic, and from republic to anarchy. The evolutionary process of religion is from pantheism to monotheism, thence to atheism, and finally to no religion. In the ultimate grand union, government becomes anarchy and religion becomes atheism." T'ai-hsü was so distressed by the unenthusiastic reception of his principles that in 1914 he retired to P'u-t'o Island, where he remained for three years. He secluded himself in the Hsi-ling temple and voraciously read Buddhist literature, Chinese classics, Western logic, philosophy and psychology, and the natural sciences. Among contemporary Chinese writers, he was particularly attracted to Chang Ping-lin and Yen Fu (qq.v.), both of whom were known for their interest in Buddhism. During this period of retreat he also began to study wei-shih, or "consciousness-only," Buddhism, a form of idealism which analyzes the mind into levels of consciousness {see Ou-yang Ching-wu). As a result of his years of study and meditation, he decided to "create a new Buddhism based on orthodox doctrines, while at the same time adopting various ancient and modern teachings of both East and West in order to enable it to meet the needs of the time." The synthetic tendency of T'ai-hsu's thinking became increasingly evident. In order to "combine and transform the various philosophies," he declared, "the world needs the doctrine of idealism." As a follower of the "consciousness-only" school, he believed all sentient things to be the products of consciousness, having no independent existence. In his opinion, this view was confirmed by Einstein's theory of relativity, "that a thing can only be identified by naming its relationship to something else." T'ai-hsü believed that man cannot live alone and that because man shares his lot with society, he must promote public welfare. Civic morality is consonant with the Buddhist view of life that advocates concern for the welfare of others. Like many of his countrymen, T'ai-hsü thought that the First World War testified to the bankruptcy of Western civilization and of Christianity. In order to establish a new moral standard for the world, he said, Buddhists must not use religion as an escape but must enter into the world to practice a new Buddhism which would be humanistic, scientific, demonstrative, and universal.

In 1918 T'ai-hsü made a preaching tour of Taiwan, and he visited Japan before returning to China. His observations during that trip reinforced his conviction that reforms were needed in the Buddhist sangha, or order. He called for elimination of commercialism and illiteracy and for higher intellectual and spiritual standards for the clergy. He held that monks should engage in productive labor, religious ceremonies should be simplified, and temples and monasteries should be reserved for meditation and research. A national monastery should be established in China to serve as a model for the new monastic ideals. He also envisaged the building of a national center of Buddhist learning in Nanking and the creation of a network of Buddhist institutes throughout the country, with parishes and chapels for preaching in every city.

Also in 1918 T'ai-hsü, Chang Ping-lin, and Chiang Tso-pin (q.v.) founded the Chueh-she [enlightenment society], which aimed at propagating the Buddhist faith. It conducted research on Buddhism and on the practice of meditation, and published a quarterly edited by T'ai-hsü, the Chueh-she chi-k'an [enlightenment journal]. T'ai-hsü soon organized a similar group in Hangchow. About 1920 he closed down the Chueh-she in Shanghai, converted the Chüeh-she chi-k'an into the Hai-ch 'ao-yin yüeh-k'an, and moved to Hangchow to devote himself to editing the Hai-ch' ao-yin. It became China's outstanding Buddhist journal and commanded high respect among Chinese scholars of all religions. In 1922 he accepted an invitation to head the newly established Wu-ch'ang fo-hsueh yuan [Wuchang Buddhist institute], an education center for monks and laymen. The institute, which was famous for its library of over 40,000 books and its lecture program, and the China Institute of Inner Learning, founded by Ou-yang Ching-wu (q.v.), became rival centers of the "consciousness-only" school of Buddhism. During the 1920's T'ai-hsü engaged in polemical debates with Ou-yang Ching-wu, who opposed his synthetic program and advocated strict adherence to traditional Buddhist tenets. In 1 922 T'ai-hsü established the Hankow Buddhist Society, which by 1933 claimed a membership of 30,000.

During a symposium on Buddhism held at Lushan, Kiangsi, in 1923, T'ai-hsü announced the establishment of the Shih-chieh fo-chiao lien-ho hui, or World Buddhist Association. In the summer of 1924 a conference of the newly established association called for a meeting of East Asian Buddhists in 1925. In the meantime, T'ai-hsü made plans for establishing a university through which Chinese Mahayana Buddhism might be introduced to the West. He instituted the annual World Conference on Buddhism in Kuling, sent his disciples to study in various Buddhist centers, and invited Buddhist leaders from abroad to lecture at the Wu-ch'ang fo-hsueh yuan. In the winter of 1 925 he led a Chinese delegation of 26 members to the East Asian Buddhist Conference held in Japan, where he delivered a series of lectures on Buddhism. The following year, at the suggestion of Hsiung Hsi-ling (q.v.) and Chang Ping-lin, he founded the Association for Buddhist Education in Asia (later the Association for Buddhist Education in China). He also established the journal Hsin-teng [inner light] and, at the invitation of overseas Chinese, gave lectures in Singapore.

Although he was depressed by the recurrent civil wars in China, T'ai-hsü continued his efforts to create a world-wide Buddhist movement. He believed that the West was more dynamic than the East, and he concluded that it would be feasible to influence the East by first influencing the West. Thus, he made a trip to Europe and the United States in 1928-29 to assess the possibilities of introducing Buddhism to the West. He first visited Germany and France with the idea ofsetting up a world university in Europe for Buddhist studies. This plan failed, but T'ai-hsü did succeed in establishing a branch of the World Buddhist Association in Paris. In England he met Bertrand Russell, with whom he discussed problems of Buddhism; and in the United States, he lectured at Columbia, Yale, and other universities. According to T'ai-hsü, his travels abroad led him to reevaluate Western civilization. He had regarded the West as being superior to the East only in material achievements, but after this trip he decided that this view was an over-simplification. In 1929 T'ai-hsü founded a new national organization, the Chung-kuo Fo-chiao hui [Chinese Buddhist society], with the aim of enlisting all Chinese temples and monasteries in the cause of reforming the order. He founded the College for Buddhist Teachings at Peiping in 1930, but he soon had to close it because of financial difficulties. In the early 1930's he established the Sino-Tibetan Buddhist Institute at a monastery near Chungking, and in 1935 he founded the College of Pali Tripitaka at Sian. He became head of the Min-nan fohsueh yuan [Minnan Buddhist institute] at Amoyin 1937. T'ai-hsu's teaching methods were considered unorthodox, for he encouraged his students to study other subjects besides Buddhism and to attempt to understand the meaning of the Buddhist sutras rather than merely memorize them.

After the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese war, T'ai-hsü moved to Szechwan, where he remained until 1945. His headquarters was at the Sino- Tibetan Buddhist Institute near Chungking. He reestablished the Wu-ch'ang fo-hsüeh yuan and the Chung-kuo fo-chiao hui in Chungking and directed their activities throughout the war years. In 1939 and 1941 he left Szechwan for a short time to lead Chinese Buddhist missions to Southeast Asia, where the group visited Buddhist centers in Burma, Malaya, Ceylon, and India. In addition to lecturing and writing, T'ai-hsü helped organize medical relief work and promoted social welfare projects in Szechwan. After the Japanese surrender in 1945, T'aihsü returned to Nanking and became the chairman of the Buddhist Reform Committee. From 1944 until his death, he also served as an executive director of the Institute of Philosophy of Life, headed by the Roman Catholic bishop Paul Yu Pin (q.v.). In 1947, after a lecture trip to Ningpo, T'ai-hsü retired to Shanghai. He became ill and died on 17 March 1947. Among T'ai-hsu's important writings are the Fo-hsüeh kai-lun [introduction to Buddhology] of 1926, the Fo-chiao ming-tsung-p 'ai yuan-liu [origins of the most eminent Buddhist sect] of 1930, the Fo-chiao tui-yü Chung-kuo wen-hua chih ying-hsiang [influence of Buddhism on Chinese culture] of 1931, the Che-hsueh [philosophy] of 1932, and the Fo-ch'eng-tsung yao-lun [essential discourse of Buddhist patriarchs] of 1940.

太虚

原名:吕沛林 法号:唯心

太虚(1890.1.8—1947.3.17),唯识宗和尚,致力于佛教的改革和现代化。主持武昌佛学院,主编《海潮音》,创办了世界佛教协会等组织。

太虚原籍浙江崇德,生在海宁的一个贫苦家庭。他父亲是一个瓦匠,在太虚一岁时就死了,他母亲于太虚五岁时再嫁。太虚由海宁的外祖父和舅父抚养。舅父是一名垫师,太虚从他受学,又常与外祖母去当地佛寺进香。

太虚十五岁时因经济困难,被迫在一个小商店当伙计,不久弃业为僧,尔后进了宁波附近的天童寺,1906—1910年间习诵佛典,注重天台宗华严宗教义。约于1908年他结识了几个热心改革的和尚,在他们的敦促下,他开始读康有为、梁启超、谭嗣同、章炳麟、邹容、严复的文章及革命党人在日本秘密出版的《民报》。1910年,太虚去南京,随佛学出版社的杨文会受业,杨是一个知名的佛教居士。1911年,他去广州,与革命党人发生联系,同时在读了托尔斯泰、巴枯宁蒲鲁东、马克思等人著作的中译本后,对无政府主义和社会主义发生了兴趣。他一度曾参加过一个讨论社会主义的团体,认为中国需要进行社会革命。

太虚对社会主义学说的兴趣影响到他对佛教教义的理解并促使他打算在国内开展一个新佛教运动。他认为佛教和社会主义是相似的,因为二者都主张社会平等和解救众生。但是,他又认为中国的佛教已因教规松弛而堕落无力实现这个目标。僧徒无知,庙产为少数人占有,古代的佛教教义对二十世纪的中国社会环境已不适合。因此经义需要用新思潮重新阐发。佛教已招致公众敌视,寺院已破落,庙产常有被政府没收的危险。他于是着手从三个方面进行改革:更新僧侣,重募寺产,重新解释教义。大约在1909年他去宁波协助创办佛教教育会,1910年在广州创办佛教教育改进会。

1912年他参加创立了佛教协进会,在镇江召开的首次会议上,他提出了宗教改革的原则。他认为庙产是信徒的共同财产,应该用于促进社会福利,特别是教育事业。他发表了一个引起激烈争论的声明,在这个声明中他主张宗教团体在用人方面应实行量才录用和按工作成绩给予报酬的原则。此外,他主张重新解释教义,因为他认为佛教是为现实世界服务的宗教。他认为佛教的演变是与政治生活的演变相适应的,宗教与政府应该有一个共同目标:建立大同世界,人们在其中各尽所能各取所需。1913年时,他写道;“政治的演进过程是从部族到皇权,从皇权到共和,从共和到无政府。宗教的演进过程是从泛神论到一神论,从一神论到无神论,最后宗教归于消灭。在最后的大同世界里,政治上是无政府,宗教上则是无神论。”

太虚因为他的主张很少为人接受而深感失望,1914年他隐居普陀岛达三年之久。他在雪林寺贪婪地阅读佛教著作,中国经典、西方逻辑、哲学、心理学和自然科学的书籍。在当代作品中,他对章炳麟、严复的著作特别感兴趣,这两人也是对佛学深感兴趣的。在这段隐居期间,他也开始研究佛教中的“唯识宗”,这是将意识分析成为不同阶段的感觉的一种唯心主义。经过几年研究思索,他决定“创立一种以佛学正宗为基础同时吸收古今中外各种学说而使之适合于当今需要的新佛教”。

太虚的思想的综合倾向变得越来越明显了,他宣称“这个世界需要理想化的教义,这就需要综合改造各派哲学”。作为“唯识宗”的信徒,他认为一切可以感知的东西都不是独立存在的,而是意识的产物。他又进而认为这个观点已为爱因斯坦的相对论所证实,即“万物均由其与他物的联系而得以证实”。他认为人不能单独生活,而且因为他与社会共命运,因此,他必须致力于促进社会福利。公共道德观是与佛教的人生观一致的,这就是关心他人的福利。太虚和他的许多本国人一样认为第一次世界大战是西方文明和基督教破产的证明。他认为为了替世界建立新的道德标准,佛教徒不应该借宗教以逃避世界,而应该进入世界去实行一种人道的、科学的、能够加以论证的、普遍的新佛教。

1918年,太虚到台湾巡回宣教,回国前又去日本,这次旅游所得更增强了他认为佛教教规需加改革的信念。他呼吁提高僧侣的知识水准和精神境界,扫除市侩习气和愚昧无知。他认为僧侣应从事生产劳动,佛事必须简化,寺庙必须保存以作潜心修养进行研究之所,应该创建一所全国性寺庙,作为新的寺院生活的模范。他还希望在南京成立一个佛教研究中心,并在全国各地建立起研究机构网,每个城市都有讲经堂备宣讲经义之用。

1918年,太虚、章炳麟、蒋作宾还创办了旨在宣传佛教的“觉社”,它指导佛学研究和修行,并由太虚主编出版《觉社季刊》。不久,太虚又在杭州创办了相似的团体。大约在1920年,他停办了上海的《觉社》,将《觉社季刊》改为《海潮音》周刊。随后他迁居杭州,全力主编《海潮音》,这是中国一本有名的佛教杂志,为国内各派宗教学者所称道。1922年,太虚应聘主持新成立的“武昌佛学会”,这是一个佛教僧侣和居士的教育中心,它以拥有四万余册图书和讲经计划而知名,它和欧阳竞无的“支那内学院”,成为唯识宗的两个旗鼓相当的佛学中心。在二十年代,太虚和欧阳竞无展开辩论,欧阳竞无反对他的综合论而主张严守佛教旧规。1922年,太虚在汉口创办佛教会,它在1933年宣称拥有会员三万人。

1923年在江西庐山召开的佛教讨论会上,太虚宣布建立世界佛教联合会,1924年夏,该会举行大会时号召于1925年召开东亚佛教会,当时,太虚打算创办一所大学,由它把中国的大乘佛教介绍到西方去。他在牯岭召开了世界佛教年会,派出他的弟子到各地的研究中心,并从国外聘请佛教界首领到武昌佛学会讲经。1925年冬,太虚率领二十五名代表去日本参加东亚佛教大会,作了一系列讲演。翌年,经由熊希龄、章炳麟建议,太虚创办了亚洲佛教教育会。他还创办《心灯》杂志,并应华侨邀请去新加坡讲学。

太虚虽为国内内战的频繁而感到沮丧,但仍致力于创立世界佛教运动。他认为西方比东方更有活力,因此先向西方施加影响,转过来再影响东方这种做法是可取的。于是,1928—29年,他去欧美旅游了解向西方介绍佛教的可能性。他先到德国、法国,想在欧洲创办一所研究佛教的世界性大学。这个计划未能实现,但是却在巴黎成功地设立了世界佛教协会分会。他在英国遇见罗素,和他讨论了佛教问题。他到美国在哥伦比亚、耶鲁等大学讲演。据太虚自述,他的国外之行使他对西方文化有了新的评价。先前,他曾认为西方仅仅在物质成就方面超过东方,而这时他认识到原来的观点过于简单化了。

1929年太虚成立了一个新的全国性的中国佛教会,目的在于登记全国大、小寺庙以便进行改革。1930年他又在北平创办佛教学院,但不久因经费困难而关闭。三十年代初,他在重庆附近的一个寺庙里创办了汉藏佛教研究所。1935年在西安创办三藏经学院。1937年他在厦门任闽南佛学院长。太虚的教学方法被认为是非正统的,他鼓励学生研究佛教以外的其他课目,以加深对佛教经义的理解,而反对单纯背诵经文。

中日战争爆发后,太虚迁住四川直至1945年,他以重庆附近的汉藏佛教研究所作为活动中心,还在重庆重建武昌佛学院和中国佛教会,在整个战争期间指导了它们的活动。1939—41年间,他一度率领佛教代表团去东南亚,访问了缅甸、马来亚、锡兰、印度等地的佛教中心。太虚除讲课、著述外,还在四川协助组织医疗救济工作和促进社会福利设施。

1945年日本投降后,太虚回到南京任佛教改革委员会主席。从1944年起到太虚去世时,他一直担任罗马天主教主教于斌主办的人生哲学研究所所长之职。1947年,他去宁波讲学后隐居在上海,随后患病于同年3月17日去世。

太虚的主要著作有1926年出版的《佛学概论》,1930年出版的《佛教各宗宗派源流》,1931年出版的《佛教对于中国文化之影响》,1932年出版的《哲学》和1940年出版的《佛正宗要论》。