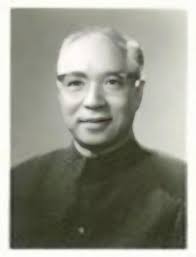

Feng Ch'eng-chün (1887-9 February 1946), historian and translator, was best known for introducing Western methods of historiography to the study of Chinese history in China through his translations of the works of European sinologists and Orientalists.

Hsiak'o, Hupeh, was the birthplace of Feng Ch'eng-chün. After receiving a traditional education in the Chinese classics, he went to Europe in 1903 at the age of 17. He studied at the University of Liege in 1905-6 and at the University of Paris from 1906 to 1910, majoring in law. After graduation in 1910, he attended the College de France. In Paris, Feng used his spare time to tutor French students of sinology in Chinese. Thus, he became acquainted with several noted sinologists, who gave him copies of their books and articles. These provided the basis for much of his later translation work. Feng was interested in the history of Chinese legal institutions, and he began to investigate such problems as foreign influences on Chinese cultural and material life and the evolution and development of Chinese institutions. He believed that a knowledge of the foreign institutions and cultures which had influenced China was a prerequisite for the study of the history of Chinese institutions. For instance, he held that the elimination of mutilation as a punishment in the sixth century in China was primarily due to the transmigration and cause-and-effect doctrines of Buddhism.

After spending some eight years in Europe, Feng Ch'eng-chün returned to China in 1911 and served for a year as secretary of diplomatic afl'airs in the Hupeh provincial government. He then became secretary of the new Parliament when it convened in Peking in 1913. When the Parliament was dissolved in 1914, he was transferred to the ministry of education as an assistant secretary in the bureau of higher and special education at Peking, where he served from 1914 to 1927. He also lectured at National Peking University from 1920 to 1926 and at National Peking Normal University in 1928-29.

Although Feng translated a number of Western works on social and political philosophy, such as Gustave LeBon's Les opinions et les croyances [I-chien yü hsin-liang), La desequilibre du monde (Shih-chieh chih fen-luan) , and La psychologie politique {Cheng-chih hsin-li), his most important work was the translation of Western sinology and Oriental studies, through which he introduced Western methods of historiography to the study of Chinese history in China. The first work he translated was Edouard Chavannes' Les voyageurs chinois (Chung-kuo chih lü-hsing chia), a booklet about Chinese travelers to foreign lands from the Han to the early Ch'ing periods. When it was presented to him by Chavannes in Paris, Feng paid little attention to it because it was a translation from Chinese sources and thus did not appear to merit careful reading. After he became engaged in teaching and research, however, he was confronted with many difficulties, especially the identification of non- Chinese names which appeared in Chinese histories and literature. Some of these names were identified in Chavannes' work. Feng discovered that some Western studies of Chinese history were not merely translations; rather, they represented a new discipline which could contribute to Chinese scholarship. Thus, he decided to translate this work of Chavannes into Chinese with his comments "to show students an example of methods of research." The translation was published in 1926. For several years, Feng continued to translate French works, especially those dealing with Chinese intercourse with Southeast Asia and with China's northwestern regions. In 1930 and 1931 he published translations of two articles by Gabriel Ferrand, '"Le K'ouen-louen et les anciennes navigations interoceaniques dans les mers du Sud" ("K'un-lun chih Xanhai ku-tai hang-hsing k'ao") and "L'Empire sumatranais de Crivijava" ("Su-men-ta-na kukuo k'ao"). Others works translated by Feng between 1928 and 1933 were Georges Maspero's La Royaume de Champa (Chan-p'o shih), Gustave Schlegel's "Les peuples etrangers chez les historiens chinois" ("Chung-kuo shih-ch'eng chung wei-hsiang chu-kuo k'ao-cheng"), Victor Segalan's "Premier expose des resultats archeologiques obtenus dans la Chine occidentale par la Mission Gilbert de Voisins" ("Chung-kuo hsi-pu k'ao-ku chi"), and Joseph Mullie's "Les anciennes villes de I'empire des Grands Leao au royaume mongol de Barin" ("Tung-mengku Liao-tai chiu-ch'eng t'an-k'ao chi"). Feng corrected and commented on the Western studies and carefully rendered into Chinese many non-Chinese names which had been identified in them.

Feng's interest in the identification of non- Chinese names in Chinese sources also led him to study Western works on Buddhism, which contain a rich vocabulary of Sanskrit names that are useful for reading Buddhist terms in Chinese. He pointed out that Chinese Buddhist literature frequently had been used by European and Japanese scholars as a source of historical information not available elsewhere, but that it had been neglected by Chinese scholars. Accordingly, in the winter of 1927 he took a month to translate an article on the 16 Lohans by Sylvain Levi and Edouard Chavannes, "Les Seize Archat" ("Fa-chu-chi chi so-chi O-lou-han k'ao"), after spending more than a year in searching and checking the sources.

Most of Feng's other early translations and writings relate to Buddhism, including the Etudes Bouddhiques {Fo-hsUeh yen-chiu), by Przyluski, Levi, and Pelliot, which was published in 1928; Li-tai cKiu-fa fan-ch'ing lu, published in 1934, a collection of 200. biographies of translators of Buddhist sutras from Han to T'ang, based on Chinese sources supplemented by recent Western studies; and Levi's several works on the lankara, mahamayuri, and saddharma smrityupasthana sutras. Feng's interest in the history of other foreign religions in China is indicated by his several books and articles on Manichaeism and Xestorianism and on the Jesuits in China.

Although most of these works were published after 1929, all of the manuscripts were completed before that year. In 1929 Feng suffered a stroke which paralyzed him. He could not mov^e without help and had to give up teaching. When his health improved, he received grants from the China Foundation for the Promotion of Education and Culture (1 932-39j to translate a number of Western works on Chinese relations with other countries and on Mongol history. During the period from 1930 to 1936, he produced no fewer than 20 monographs. These included translations of Paul Pelliot's "Deux itineraires de Chine en Inde a la fin du VHIe siecle" iChiao-kuang Yin-tu liang-tao k'ao), Leonard Aurousseau's La premiere conquete Chinoise des pays Annamites {Ch'in-tai ch'u-p'ing Nanyüeh k'ao), Edouard Chavannes' Documents sur les Tou-kiue ( Turcs) occidentaux [Hsi T'u-chueh shih liao), sections dealing with the Mongols in Rene Grousset's Histoire de rextreme-orient [Alengku shih lüek), D'Ohsson's Histoire des Mongols {Meng-ku shih), Lucien Bouvat's Timour et les Timourides [T'ieh-mu-erh ti-kuo), Pelliot's "Les grandes voyages maritimes chinois au debut du XVe siecle" {Cheng Ho hsia hsi-yang k'ao), A. J. H. Charignon's Le livre de Marco Polo [Ma-k'o-po-lo hsing-chi), and the first 50 biographies in Louis Pfister's Notices biographiques et bibliographiques sur les jesuites de I'ancienne mission de Chine [Ju hua yeh-su-hui shih lieh-chuan). He also wrote two books on Mongol history: Yuan tai pai-hua pei (1933), a study of some 30 colloquial versions of Mongolian edicts in stone inscriptions, and the Ch'eng-chi-ssu-han chuan (1934), a biography of Chingis Khan. His translations of articles on the history and geography of Central Asia and the South Seas were included in two collections, the Shih-ti ts'ung-k'ao (1931-33) and the Hsi-yü nan-hai shih-ti k'ao-cheng i-ts'ung (1934-56). Almost all of Feng's works were published by the Commerical Press in Shanghai. After 1936 Feng did not produce many translations, but devoted his time to writing and to collating and editing early Chinese works on foreign travels—the major, sometimes the only, contemporary records of many of the countries of Southeast and South Asia. These include his collation of two texts of early fifteenth-century travels, the Ying-yai sheng-lan by Ma Huan and the Hsing-ch'a sheng-lan by Fei Hsin, two accounts by men who accompanied Cheng Ho on his famous maritime expeditions to the South Seas between 1405 and 1433. These were published in 1935 and 1936, respectively. He also published editions of the Chu fan chih by the thirteenth-century author Chao Ju-kua, which is the most comprehensive account of the foreign countries and of various products traded from abroad during Sung times, and the Hai lu, a travel record based on the observations of Hsieh Ch'ing-kao ( 1 7651821), a Chinese who worked for 14 years on Western ships and who visited several Western countries. Both of these appeared in 1937. Feng also collated several other works, including the Hsi-yang ch'ao-kung tien-lu, a record of foreign tribute missions to China, but none of these manuscripts were published.

One of Feng's major compilations during this period was the Chung-kuo nan-yang chiao-t'ung shih, published in 1937, a comprehensive treatise on Chinese intercourse with Southeast and South Asia from Han to Ming times and a historical account of individual countries in this area. He also compiled two dictionaries of geographical names. These were the result of his lifelong research in matching foreign names transcribed in European languages with those transliterated in Chinese sources. Hsi-yü timing, a bilingual list of place names from Central and Western Asia to Europe and Africa, was published in 1930 by the Sino-Swedish Expedition to the Northwest and again in 1 955 from a revised manuscript. Feng's work on the South Seas, "Nan-hai ti-ming," which covers Southeast and South Asia, was not published.

Because of Feng Ch'eng-chün's physical disabilities, after 1931 his translations and writings were dictated by him to his eldest son, Feng Hsien-shu, a graduate of Fu-jen University who died in 1943 after his arrest by the Japanese for participation in anti-Japanese activities. Some of his later writings were dictated to his second son, Feng Hsien-chi, who is mentioned as Shuyin in his father's books written after 1935. Although many of Feng Ch'eng-chün's friends and several of his children moved to the interior during the war years, he remained in Feiping because of his physical condition. During this period he contributed only a few articles to journals. In 1945, when the universities moved back from west China and a temporary associated university was set up in Peiping, he was appointed a professor of history. He held this position for only a short time; he died of a kidney infection in February 1946 at the age of 60. Feng had ten children, five sons and five daughters.

冯承钧 字:子衡

冯承钧(1887—1946.2.9),史学家和翻译家,他翻译了一些西方学者的汉学和东方学著作,由此介绍了西方的史学研究方法。

冯承钧生在湖北夏口,他在国内受了些旧式教育后,1903年十七岁时就到欧洲去了。1905—1906年在比利时列日大学,1906—1910年在巴黎大学,主修法律学。1910年毕业后,进法兰西学院。冯承钧在巴黎的业余时间,用中文

指导法国的汉学研究者,因此认识了一些知名的汉学家,他们赠送他著作和论文。

冯承钧对中国的法制史感兴趣,开始研究中国文化与物质生活及中国制度演变发展中的外来影响。他认为对中国有影响的国外的制度和外国文化史的知识,是研究中国制度史的先决条件。例如,他认为中国在公元六世纪时,废除

断肢酷刑,是受佛教轮回及因果报应教义的影响。

冯承钧在欧洲度过了八年后,1911年回国,任湖北外交司参事。1913年新国会召开时,任一等秘书,1914年国会解散,1914—1927年任北京教育部高等教育司秘书,1920—1926年在北京大学,1928—1929年在北京师范大学兼课。

冯承钧虽然翻译了一些西方社会和政治哲学的书籍,例如,勒朋的《意见与信仰》、《世界之纷乱》、《政治心理》,但是,他的重要译作是西方学者的汉学和东方学研究著作,通过这些著作,给中国的历史研究介绍了西方的史学方法。其中第一部译著是沙畹的《中国之旅行家》,这本小册子介绍了自汉至清初这一长时期内,到国外旅行的中国人。沙畹在巴黎赠送这本书的当时,冯承钧并未加以注意,认为这不过是转译中文资料不值细读。但当他从事教学与研究时,就发现了许多困难,尤其是中国文献资料中的很多非中国名称应该如何鉴定,在沙畹的著作中就鉴定出一些这种名字。因此,冯承钧认为西方学者的一些关于中国历史的研究,并不单纯是翻译,而且是对中国的学术成就提供了一种新的训练方法。他决定将沙碗的著作译成中文,并加以评述说,“这是向学者们提出了一种新的研究方法的范例”。译本在1926年出版。

此后几年中,冯承钧继续翻译法文著作,特别是关于中国与东南亚及中国西北边疆关系的著作。1930及1931年,他翻译了费琅的两篇论文:《昆仑及南海古代航行考》、《苏门答腊古国考》。1928—1933年,翻译马司帛洛的《占

婆史》,希梅勒的《中国史乘中未详诸国考证》,包伽兰的《中国西部考古记》,牟里的《东蒙古僚代旧城探考记》。冯承钧还校订注释了许多西方著述,并将其中已鉴定的非中国名称译成中文。

冯氏鉴定中国资料中的非中国名称,使他注意研究有关佛学的西方著述,其中有大量对阅读中文佛教专业名词有用的梵文名称。他指出欧洲和日本的学者通常以汉文的佛经作为别处无法得到的历史资料来源,而中国学者却并未注

意及此。因此,他在用了一年多的时间搜寻并核对材料后于1927年冬用了一个月译出了烈维的《十六罗汉考》和沙畹的《法住记及所记阿罗汉考》。冯承钧早期有关佛教的译著有普热吕司基、烈维、伯希和的《佛学研究》,1928年出版。1934年出版了《历代求法翻经录》,他以中文资料为据,又参照了西方著作,收集了自汉至唐的二百名佛经翻译高僧,还翻译了烈维的几种著作。他对中国的其它几种外来宗教的历史很注意,例如,对摩尼教、景教、耶苏会也写了专著和论文。

上述著述,差不多都在1929年以后出版,而他的原稿却早已完成。1929年,冯承钧忽然中风,无人帮助不能行动,无法教书。健康稍恢复后,由中华教育文化基金会(1932—1936年)拨款让他翻译有关中外交通史及蒙古史的

西方著作。1930—1936年间,他译出了至少二十几种专著,例如,伯希和的《交广印度两道考》,鄂卢梭的《秦代初平南越考》,沙畹的《西突厥史料》,格鲁赛著作中有关蒙古部分的《蒙古史略》,多桑的《蒙古秘史》,布哇的

《帖木儿帝国》,伯希和的《郑和下西洋考》,沙海昂的《马可波罗行记》,费赖之《入华耶稣会士列传》的前五十篇。他还写了两种蒙古史:《元代白话碑》(1933年),这是三十多种元代白话谕旨的碑刻资料,还有一本《成吉斯汗传》(1934年)。其它有关中亚和东南亚的史地论著,收集在两本集子中事《史地丛考》(1931—1933年),《西域南海史地考证译丛》(1934—1956年)。冯承钧的全部译著几乎全部由上海商务印书馆出版。

1936年后,冯承钧的翻译不多,而专注于校订中国古代国外游记的著作,这些是现在有关东南亚及南亚主要的、有时还是仅有的记载。例如,马欢的《瀛涯胜览》,费信的《星槎胜览》。这是两位随同郑和在1405—1433年下西洋的使者。这些都分别出版于1935及1936年。他还校订了十三世纪作者赵汝适的《诸蕃志》,这是宋代对外国及与海外进行贸易各种商品最详细的记载。还有谢清高(1765—1821年)的《海录》,此人曾在西方船舶上工作了十四年,到过许多西方国家。这些工作都是1937年前完成的。他还校注了《西洋朝贡典录》,这是来华朝贡使节的纪录,这些稿件都未发表。

冯承钧的一种重要著作《中国南洋交通史》,已于1937年出版,详尽记述了自汉至唐中国和东南亚、南亚诸国交往的历史资料。他还编了两本地名辞典:《西域地名》,列举从中亚、西亚到欧、非两洲的地名,曾于1930年由中

瑞(典)考察团出版,1950年又修订出版。还有一本是《南海地名》,包括东南亚和南亚地名,未出版。这是他毕生从事的工作,把欧洲文字所记(国外)的地名与中国资料中的译音加以校订对比。

冯承钧由于身体不能行动,自1931年以后,他的译著都由他口授、而由他辅仁大学毕业的长子冯先恕笔录。此人因参加抗日活动,于1943年被日军逮捕,以后则由次子冯先祺笔录,冯承钧在1935年著作中提到的就是他。抗日战

争期间,冯承钧的不少朋友和几个儿女都迁往内地,他本人因身体不好留在北平。这一期间,著述很少。1945年,各大学又从西南迁回北平,他任史学教授,但为期很短。1946年二月因肾脏病去世,年六十岁,遗有子五人,女五人。